Steroid Eye Risk Calculator

Eye Safety Assessment

Find out your personalized risk of steroid-induced eye damage based on your treatment type and duration.

Long-term steroid use can silently damage your eyes - and most people don’t realize it until it’s too late.

If you’ve been on steroid pills, inhalers, injections, or even eye drops for weeks or months, your eyes might be at risk. You might not feel any pain. You might not notice your vision changing until you’re reading a license plate from 10 feet away - or you’re seeing halos around streetlights at night. That’s because steroid-induced cataracts and steroid glaucoma don’t come with warning signs. They creep in quietly, and by the time symptoms show up, damage may already be permanent.

It’s not rare. About 5 to 35% of people using steroids long-term develop eye problems. That’s not a guess - it’s from clinical studies tracked by the National Institutes of Health and the American Academy of Ophthalmology. And here’s the kicker: you don’t need to have glaucoma or cataracts before starting steroids. Nearly one-third of all steroid users experience a rise in eye pressure. About 5% of the general population are at high risk for serious damage - and many don’t even know they’re in that group.

How steroids hurt your eyes: the science behind the damage

Steroids - whether taken orally, inhaled, injected, or applied as eye drops - don’t just reduce inflammation. They also change how your eye works at a cellular level.

For steroid-induced cataracts, the problem starts in the lens. Steroids react chemically with proteins in the back of the lens, forming abnormal clumps called Schiff base adducts. These aren’t seen in regular age-related cataracts. This specific reaction leads to posterior subcapsular cataracts (PSCs), which form right at the center of the lens, right where light passes through. That’s why they blur vision so quickly - even when the cataract is still small. Unlike age-related cataracts that take years to grow, steroid-induced ones can become severe in just 2 to 4 weeks of daily use.

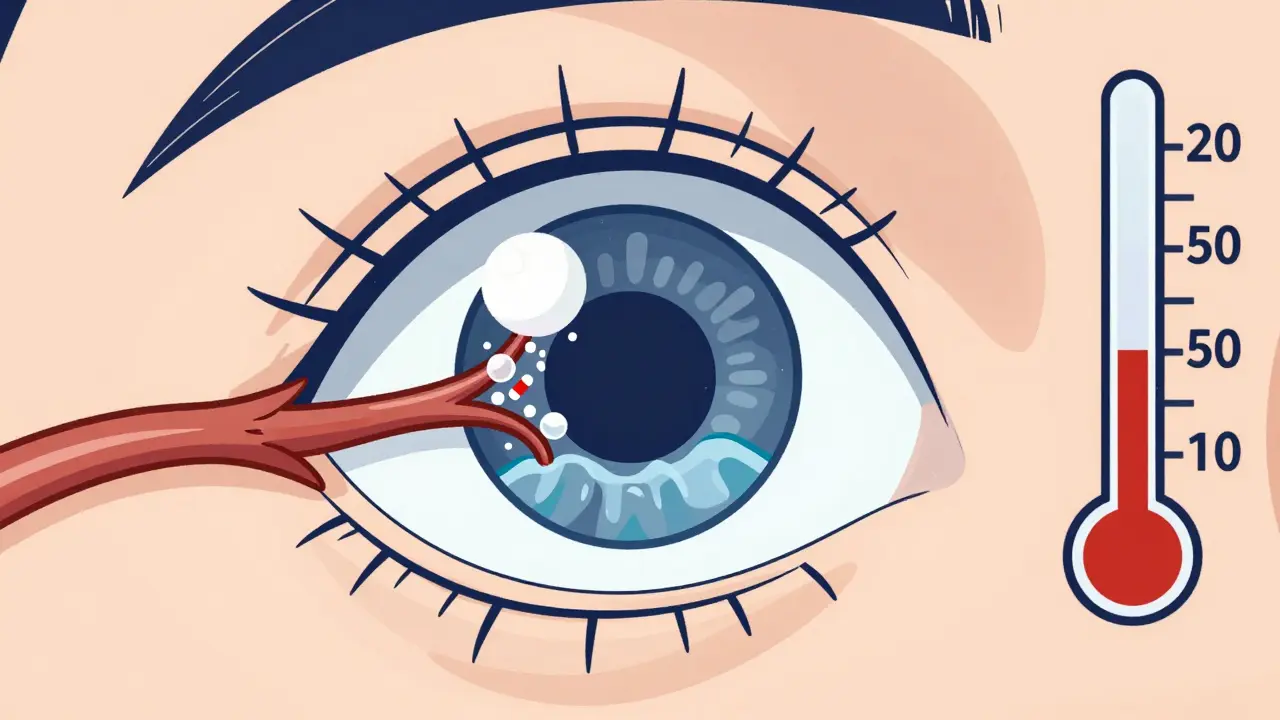

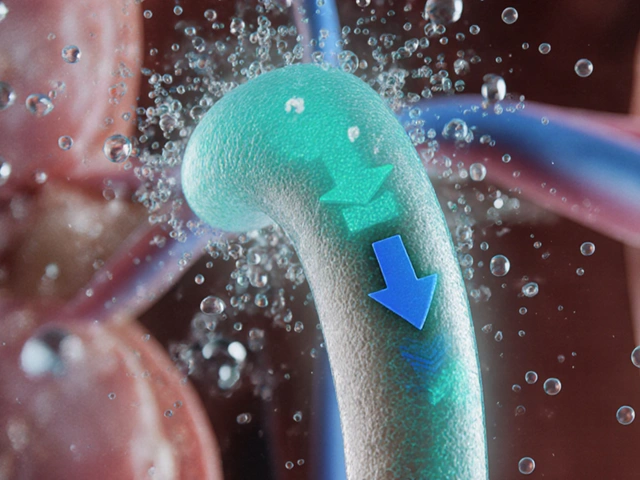

For steroid glaucoma, the issue is pressure. Steroids clog the eye’s drainage system - the trabecular meshwork - making it harder for fluid to leave. That builds up pressure inside the eye. Normal eye pressure is around 10 to 21 mmHg. Steroid use can push it up to 30, 40, even 50 mmHg in extreme cases. That pressure crushes the optic nerve over time. Once the nerve is damaged, vision loss is irreversible. The good news? If caught early, pressure can drop back to normal after stopping steroids. The bad news? Many people don’t get tested until the nerve is already gone.

Who’s most at risk - and why you can’t assume you’re safe

Not everyone responds the same way to steroids. Some people’s eyes stay perfectly fine. Others develop severe problems after just a few weeks.

Here’s who’s most vulnerable:

- People with a family history of glaucoma

- Those already diagnosed with glaucoma (up to 90% of them become steroid responders)

- Patients who’ve had cataract surgery - steroid drops are common after surgery, but they’re also a top cause of secondary glaucoma in this group

- People with diabetes or connective tissue disorders

- Anyone using steroid eye drops for more than 2 weeks

Here’s what’s scary: about 35% of steroid-induced glaucoma cases happen in people with no prior eye history. You could be perfectly healthy, have never had an eye exam, and still end up with permanent vision loss because you didn’t know to get checked.

And it’s not just about how long you’re on steroids - it’s about how you’re taking them. Topical eye drops are the most dangerous. They deliver steroids straight to the eye, bypassing your body’s natural filters. Oral steroids like prednisone take longer to cause damage - usually 3 to 6 months - but they still carry serious risk. Even inhaled steroids for asthma can raise eye pressure in sensitive individuals.

What the symptoms look like - and why you might miss them

Steroid glaucoma is called the "silent thief of sight" for a reason. There’s no pain. No redness. No sudden blur. You just slowly lose peripheral vision - the kind you use to see a car coming from the side, or to walk through a crowded room without bumping into things.

For cataracts, symptoms are more obvious - but still easy to ignore:

- Cloudy or blurry vision - like looking through a fogged-up window

- Colors look faded or yellowed

- Glare or halos around lights - especially at night

- Needing brighter light to read

- Frequent changes in eyeglass prescription

One patient on Reddit shared: "After six months of prednisone for asthma, my eye doctor found advanced posterior subcapsular cataracts - I had no idea until my vision test showed 20/80 acuity." That’s legally blind in many places. And he wasn’t even on eye drops.

Another person wrote on Healthgrades: "I didn’t realize my steroid eye drops for uveitis were causing glaucoma until I lost peripheral vision - now I need multiple daily eye drops permanently." That’s the reality for too many people.

How to protect your eyes - step by step

The good news? Almost all steroid-related eye damage is preventable - if you know what to do.

Step 1: Get a baseline eye exam before starting steroids. This isn’t optional. Your eye pressure, optic nerve health, and lens clarity should be recorded before any steroid treatment begins. If you’re already on steroids and haven’t had one, get it done now.

Step 2: Monitor your eye pressure regularly. The NIH recommends:

- Check IOP at 2 weeks after starting steroids

- Then every 4 to 6 weeks for the first 3 months

- After that, every 6 months if pressure stays normal

If your pressure rises more than 5 mmHg from baseline, your doctor needs to act - even if you feel fine.

Step 3: Use the lowest dose for the shortest time possible. Don’t assume "a little bit" is safe. Even low-dose steroid eye drops used daily for 4 months can cause posterior capsular opacification - a type of cataract that requires surgery.

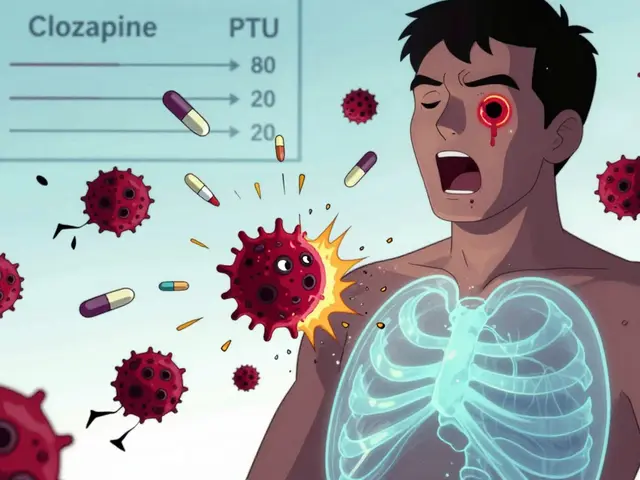

Step 4: Ask about alternatives. Are there non-steroid anti-inflammatories that could work? Loteprednol etabonate, for example, is a newer steroid that’s been shown in 2024 JAMA Ophthalmology studies to cause significantly less pressure rise than traditional steroids like prednisolone.

Step 5: Know your family history. If a parent or sibling has glaucoma, tell your doctor. Genetic testing for steroid responsiveness is now available in research settings and may become routine within the next few years.

What your doctor should be doing - and what they often aren’t

Here’s the broken part of the system: only 42% of primary care doctors routinely refer patients on long-term steroids for eye exams. That means over half of people at risk are flying blind.

Doctors often focus on the reason you’re on steroids - asthma, lupus, arthritis - and forget the eyes. But your eye doctor isn’t going to know you’re on steroids unless you tell them. And your primary care doctor might not know to check.

So here’s what you need to do: Be your own advocate. Say this at your next appointment:

- "I’m on steroids. Can you check my eye pressure?"

- "Has my optic nerve been examined?"

- "Could I have steroid-induced cataracts?"

If your doctor says, "You’re fine," ask for a referral to an ophthalmologist. Don’t settle for a quick glance. You need a full dilated eye exam - not just a pressure check.

The bottom line: You can’t afford to wait

Steroids save lives. They help people with autoimmune diseases, severe asthma, and chronic inflammation breathe, move, and live. But they also carry a hidden cost - your vision.

There’s no magic pill to reverse steroid damage. Once the optic nerve is destroyed, it’s gone. Once the cataract clouds your lens enough, surgery is the only fix - and surgery doesn’t undo nerve damage from glaucoma.

But here’s the hope: if you catch it early, you can stop it. Studies from the Glaucoma Research Foundation show that with proper monitoring, vision-threatening complications drop by 70 to 80%.

So if you’re on steroids - even if you feel great - get your eyes checked. Don’t wait for blurry vision. Don’t wait for halos. Don’t wait for pain. Because by then, it might be too late.

Donna Packard

18 December, 2025 . 06:02 AM

I never realized how silent this damage could be. I’ve been on prednisone for lupus for two years, and I’ve never had an eye exam since I started. I’m scheduling one this week.

Sachin Bhorde

19 December, 2025 . 12:51 PM

yo i got steroid eye drops for uveitis last year and my doc never warned me abt pressure spikes. i went blind in one eye for 3 days then it went back. turns out my iop was 42. never again. get checked.

Peter Ronai

21 December, 2025 . 10:45 AM

This is such a basic medical fact, yet people act like it’s groundbreaking. You don’t need a Reddit post to know that steroids raise IOP. Any med student learns this in week two of ophthalmology. The real issue is lazy doctors, not lack of awareness.

Steven Lavoie

22 December, 2025 . 03:30 AM

The science presented here is remarkably accurate. The biochemical mechanism of Schiff base adduct formation in posterior subcapsular cataracts is well-documented in the Journal of Cataract & Refractive Surgery, 2021. Similarly, the trabecular meshwork obstruction pathway has been validated through confocal microscopy studies. This post deserves more attention from primary care protocols.

Raven C

23 December, 2025 . 10:37 AM

It’s profoundly disturbing that the medical establishment continues to treat steroid-induced ocular pathology as an afterthought. The systemic negligence-particularly among primary care physicians-is not merely oversight; it is a failure of professional duty. One cannot ethically prescribe corticosteroids without mandating baseline and serial tonometry. This is not a suggestion-it is a standard of care.

Brooks Beveridge

23 December, 2025 . 23:02 PM

You're not alone. I was on high-dose prednisone for 8 months after a transplant. I felt fine. Then one day, I couldn't read my phone. Turns out: PSC cataracts + elevated IOP. Got surgery. Lost some peripheral vision. But I'm alive and I'm vigilant now. You got this. Check your eyes. 💪👁️

Anu radha

24 December, 2025 . 15:55 PM

I am from India. My mother used steroid drops for eye allergy. She lost vision. No one told us. Please tell more people. Eyes are very important.

Joe Bartlett

25 December, 2025 . 21:51 PM

Bloody hell, mate. My mate’s mum went blind because she didn’t get checked. Just get your eyes seen. It’s not hard.

Marie Mee

26 December, 2025 . 12:08 PM

I think this is all part of the pharmaceutical agenda. They know steroids cause damage but they want you to keep using them so you need more drugs and surgeries. The eye doctors are in on it too. They profit from cataract ops. I stopped all meds after this. Now I use turmeric and sunlight. My vision is better than ever.

Jigar shah

26 December, 2025 . 12:59 PM

Interesting. In India, steroid eye drops are sold over the counter without prescription. Many people use them for redness or itching. This post should be translated and shared widely. We need public awareness campaigns.

Michael Whitaker

26 December, 2025 . 14:36 PM

I’m sorry, but I have to say this: if you’re on steroids long-term and haven’t had a dilated fundus exam, you’re not just negligent-you’re reckless. I’m not judging you. I’m judging the system that lets this happen. And I’m judging the doctors who don’t follow up. I’ve seen three patients lose their sight because no one said a word. You’re not safe. You’re not fine. Get checked.