Diabetes Eye Infection Risk Calculator

Personal Risk Assessment

Did you know that high blood sugar can turn a harmless eye irritation into a painful, vision‑threatening infection? Bacterial eye infections are caused by microscopic germs that invade the surface of the eye, and people with diabetes are especially vulnerable because their immune system and tear film don’t work as well.

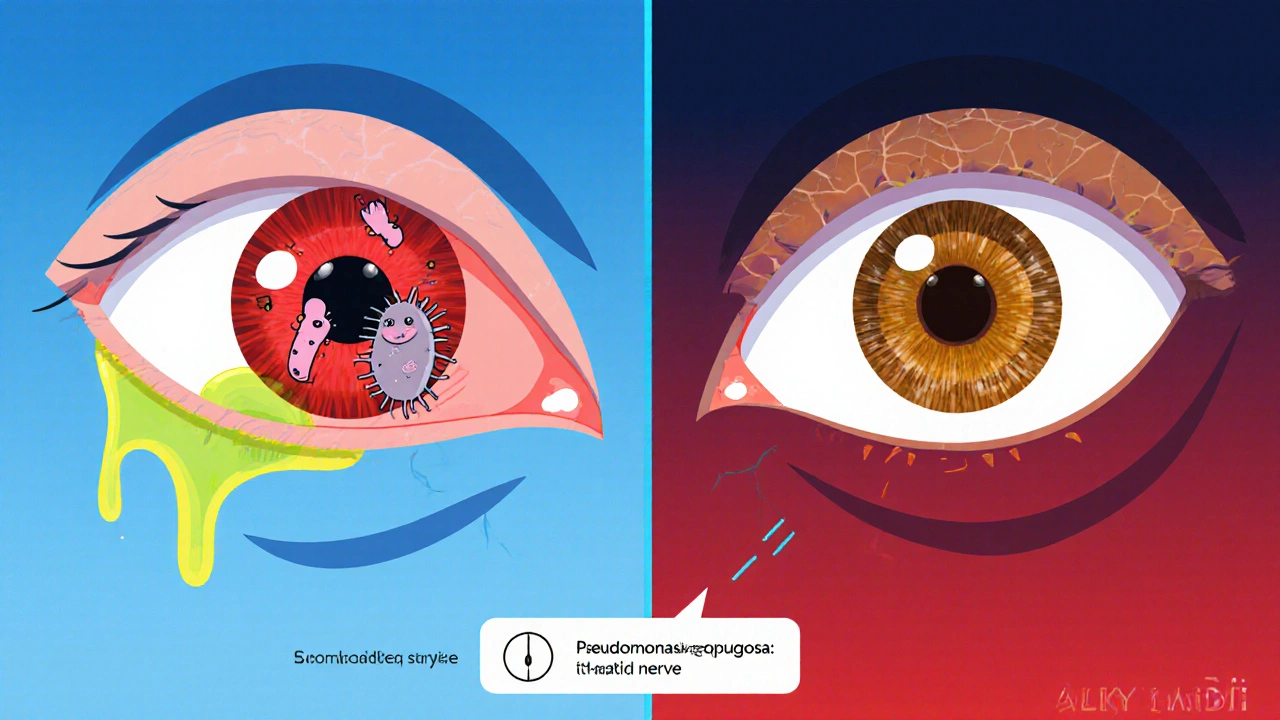

What Exactly Is a Bacterial Eye Infection?

In the simplest terms, a bacterial eye infection (sometimes called bacterial conjunctivitis or bacterial keratitis depending on the part of the eye involved) is an invasion of the eye’s outer layers by bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, or Pseudomonas aeruginosa. These microbes multiply quickly, trigger inflammation, and produce the classic signs of redness, discharge, and discomfort.

Why Diabetes Makes Your Eyes More Susceptible

When you live with Diabetes, several factors line up to give bacteria a foothold:

- Elevated blood glucose creates a sugary environment in the tear film, which bacteria love.

- Reduced immune response-high glucose impairs white blood cell function, so the eye can’t fight off invaders as fast.

- Dry eye syndrome is common in diabetics; a dry surface lacks the protective mucus layer that normally washes away microbes.

- Peripheral nerve damage (diabetic neuropathy) can dull the sensation of irritation, letting an infection grow before you notice it.

Common Bacterial Eye Infections and Their Traits

| Infection | Usual Bacteria | Main Symptoms | Standard Treatment | Risk for Diabetics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conjunctivitis (pink eye) | Staphylococcus aureus, Haemophilus influenzae | Redness, watery or purulent discharge, gritty feeling | Topical antibiotic drops (e.g., erythromycin) | Higher incidence; slower healing |

| Keratitis (cornea infection) | Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus epidermidis | Severe pain, blurred vision, light sensitivity, ulcer on cornea | Intensive fortified antibiotic drops; sometimes oral antibiotics | Can progress to corneal perforation quickly |

| Blepharitis (eyelid border inflammation) | Staphylococcus spp., Propionibacterium acnes | Scaly eyelid edges, crusting, burning sensation | Hygiene + topical antibiotic ointment | Dry eye makes it chronic in diabetics |

Spotting the Warning Signs Early

People with diabetes should keep a keen eye on any changes, because early detection can prevent permanent damage. Look out for:

- Redness that doesn’t fade after a day or two.

- Sticky, yellow‑green discharge-especially if it’s thicker than normal tears.

- Sudden increase in eye pain or a feeling that something’s stuck in the eye.

- Blurred vision that appears out of the blue, even if you wear glasses.

- Light sensitivity that feels worse than usual.

If you notice any of these, don’t wait for the infection to run its course. Prompt treatment is the best defense.

Treatment Options Tailored for Diabetics

While most bacterial eye infections respond to standard antibiotic eye drops, diabetics often need a slightly different approach:

- Choose the right antibiotic. Broad‑spectrum drops like moxifloxacin cover a wide range of bacteria and work well for the gram‑negative species that thrive in high‑sugar environments.

- Consider oral antibiotics. If the infection is deep (keratitis) or the patient’s blood sugar is poorly controlled, a short course of oral doxycycline can help clear the infection from the inside out.

- Monitor blood glucose closely. Tight glycemic control (target HbA1c < 7%) speeds up healing and reduces the chance of recurrence.

- Use lubricating drops. Preservative‑free artificial tears restore a healthy tear film, making it harder for bacteria to stick.

- Follow up with an ophthalmologist. A specialist can examine the cornea with a slit‑lamp and adjust treatment if the infection isn’t improving within 48‑72 hours.

Prevention: Simple Steps That Make a Big Difference

Prevention is especially powerful when you combine good eye hygiene with solid diabetes management:

- Keep hands clean. Wash your hands before touching your eyes or applying eye medication.

- Don’t share eye cosmetics or towels. Even a soft washcloth can spread bacteria.

- Use protective eyewear. If you work in dusty settings or swim in pools, goggles shield the eye surface.

- Stay on top of blood sugar. Regular monitoring, a balanced diet, and medication adherence reduce the sugary environment that fuels bacterial growth.

- Schedule routine eye exams. An annual retinal scan can catch early diabetic eye changes before they turn into infections.

When to Seek Professional Care

Most minor bacterial infections clear up in a few days with proper drops, but certain red flags demand immediate attention:

- Intense pain that doesn’t ease after applying drops.

- Rapid vision loss or the appearance of a white spot on the cornea.

- Persistent discharge for more than three days.

- Fever or feeling generally unwell, indicating the infection might be spreading.

- Any worsening despite using prescribed antibiotics.

In those cases, an urgent visit to an eye specialist can mean the difference between a quick recovery and long‑term visual impairment.

Key Takeaways

- Diabetes raises the risk of bacterial eye infections by creating a sugary, dry, and immune‑compromised eye surface.

- Common infections include conjunctivitis, keratitis, and blepharitis, each with distinct bacterial culprits.

- Early symptom detection, tight glycemic control, and prompt antibiotic treatment are crucial.

- Good hand hygiene, avoiding shared eye products, and regular eye exams help keep infections at bay.

- Seek an ophthalmologist if pain, vision loss, or discharge worsen after a couple of days.

Can high blood sugar alone cause an eye infection?

High blood sugar doesn’t directly introduce bacteria, but it creates a sweet environment that helps germs multiply and weakens the eye’s natural defenses, making infection more likely.

Are over‑the‑counter eye drops safe for diabetics?

Many OTC lubricating drops are fine, but for bacterial infections you need prescription‑strength antibiotics. Always check with your doctor before starting any new drop.

How long should I use antibiotic eye drops?

Typical courses last 5‑7 days, but if you have diabetes you may be advised to finish the full 10 days to ensure the infection is fully cleared.

Can I prevent eye infections with diet?

A balanced diet that keeps blood glucose stable-rich in fiber, lean protein, and low‑glycemic carbs-helps maintain healthy tear composition and supports immune function.

What’s the link between diabetic retinopathy and bacterial infections?

Retinopathy damages blood vessels in the retina, but it doesn’t cause surface infections. However, both conditions stem from poor glucose control, so managing one helps reduce the risk of the other.

Monika Bozkurt

19 October, 2025 . 15:33 PM

Maintaining optimal glycemic control serves as a cornerstone for ocular immune competence; elevated glucose impairs neutrophil chemotaxis and compromises tear film stability. Consequently, diabetic patients experience prolonged bacterial colonization on the corneal surface. A structured regimen of regular HbA1c monitoring, coupled with adjunctive lubricating therapy, can mitigate this pathophysiological cascade. Clinicians should therefore emphasize metabolic regulation as an integral component of ophthalmic prophylaxis.

Catherine Viola

20 October, 2025 . 08:13 AM

It is noteworthy that pharmaceutical companies have a vested interest in perpetuating the narrative of “standard” antibiotic courses, thereby fostering dependence on costly prescription drops. The data suggest that many over‑the‑counter formulations are deliberately under‑dosed to drive patients toward physician‑issued regimens. Moreover, the regulatory agencies have historically colluded with industry stakeholders, obscuring alternative, cost‑effective interventions. As a result, a critical appraisal of treatment protocols is essential for truly autonomous patient care.

sravya rudraraju

21 October, 2025 . 00:53 AM

Diabetes creates a multifaceted vulnerability in the ocular surface that extends beyond simple hyperglycemia, and understanding each facet empowers patients to take proactive measures. First, the hyperosmolar environment of the tear film provides an ideal substrate for bacterial proliferation, particularly for Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Second, the diminished blink reflex associated with peripheral neuropathy reduces mechanical clearance of debris and microbes, allowing colonization to persist. Third, chronic inflammatory signaling alters the expression of antimicrobial peptides, undermining innate defenses. In practical terms, a disciplined hand‑washing routine before any ocular manipulation can dramatically lower inoculum load. Complementing this, the routine application of preservative‑free artificial tears restores a stable tear film, thereby diluting potential pathogens. Patients should also schedule quarterly comprehensive eye examinations, during which slit‑lamp assessments can detect early epithelial disruptions before they evolve into full‑blown infections. When a bacterial conjunctivitis is suspected, initiating broad‑spectrum topical antibiotics such as moxifloxacin can curtail bacterial multiplication; however, clinicians often recommend extending therapy to ten days in diabetic individuals to ensure complete eradication. Oral adjuncts like doxycycline may prove beneficial for deeper stromal involvement, as they achieve therapeutic concentrations within corneal tissue. Equally important is tight glycemic control; studies consistently demonstrate that an HbA1c below 7 % correlates with faster resolution of ocular infections. Dietary modulation, emphasizing low‑glycemic index carbohydrates and adequate omega‑3 fatty acids, further stabilizes tear film composition. Regular physical activity improves microvascular circulation, indirectly supporting ocular immune surveillance. Patients should also avoid sharing makeup or towels, as these fomites can serve as reservoirs for resistant bacteria. Protective eyewear in dusty or aquatic environments provides a mechanical barrier against contaminant exposure. Finally, a multidisciplinary approach involving endocrinologists, optometrists, and primary care physicians ensures that systemic and ocular health are addressed in concert, thereby reducing the cumulative risk of infection over time.

Ben Bathgate

21 October, 2025 . 17:33 PM

Honestly, most people ignore the simplest tip-wash your hands-while blowing their own whistle about “advanced” eye drops. If you’re not scrubbing your palms before touching your eye, you’re practically inviting bacteria to a party. The reality is that even the fanciest antibiotic won’t cure an infection you’ve self‑inflicted by neglect. So cut the excuses and start with basic hygiene.

Ankitpgujjar Poswal

22 October, 2025 . 10:13 AM

Listen up: if your blood sugar spikes even once, you’re giving microbes a free buffet, and that’s unacceptable. Get your glucose under control now, and pair it with preservative‑free lubricants to rebuild that protective barrier. No more half‑measures, full commitment or you’ll pay with your sight.

Bobby Marie

23 October, 2025 . 02:53 AM

Never share towels after a workout.

Christian Georg

23 October, 2025 . 19:33 PM

Keeping your glucose stable dramatically reduces the sugar‑laden tear film that bacteria love, so regular monitoring is a frontline defense 😊. Adding preservative‑free artificial tears creates a hostile environment for microbes, helping your eyes stay clear. If you notice any redness lasting more than two days, consider a prompt ophthalmology visit to rule out deeper infection.

Christopher Burczyk

24 October, 2025 . 12:13 PM

The prevailing consensus in ocular microbiology underscores that bacterial keratitis in diabetic patients often necessitates fortified antibiotic regimens, a fact frequently overlooked by general practitioners. Empirical therapy with monotherapy may be insufficient given the propensity for multidrug‑resistant strains in hyperglycemic milieus. Consequently, a culture‑directed approach, supplemented by systemic agents, optimizes therapeutic outcomes. Practitioners must therefore integrate comprehensive metabolic assessment into their treatment algorithms.

Nicole Boyle

25 October, 2025 . 04:53 AM

From a pathophysiological perspective, the interplay between hyperosmolar tear film and compromised mucin secretion creates a niche for opportunistic pathogens. Moreover, the attenuation of secretory IgA in diabetic lacrimal secretions reduces mucosal immunity. Clinically, this manifests as persistent conjunctival hyperemia and mucoid discharge. Early intervention with broad‑spectrum fluoroquinolones can preempt stromal invasion, while adjunctive lubricants restore tear film homeostasis. Ultimately, interdisciplinary management yields the best prognostic trajectory.

Caroline Keller

25 October, 2025 . 21:33 PM

It’s infuriating how some ignore basic eye care and then blame fate for losing sight