On December 25, 1956, a baby was born in Germany with arms that looked like flippers-no hands, no elbows, just short stumps. No one knew why. That baby was the first known victim of a drug that would soon be linked to over 10,000 birth defects worldwide. The drug was thalidomide, sold as a harmless sedative and morning sickness remedy. Today, it’s a controlled cancer treatment. But its story isn’t just about science-it’s about trust, failure, and how medicine learned to protect mothers and babies.

The Rise of a ‘Miracle Drug’

In the 1950s, life felt optimistic. Antibiotics were saving lives. Vaccines were on the rise. And then came thalidomide. Developed by a German company, Chemie Grünenthal, it was marketed as a safe, non-addictive alternative to barbiturates. Doctors loved it. Pregnant women loved it even more. It eased nausea, helped with sleep, and didn’t cause drowsiness the next day-so they said. By 1959, over a million pregnant women in 46 countries had taken it. No one tested it for harm to unborn babies. Why would they? It was a sedative, not a cancer drug. It wasn’t meant for pregnancy.The First Warnings

By 1960, doctors started noticing something strange. Babies were being born with missing limbs, ears, eyes, hearts. Some had no esophagus. Others had no appendix. One doctor in Sydney, William McBride, saw three cases in one week. He started asking questions. He noticed the mothers had all taken thalidomide during early pregnancy. He wrote to The Lancet in June 1961: “I believe thalidomide is the cause.” At the same time, in Germany, Widukind Lenz, a pediatrician, was seeing the same pattern. He called Grünenthal on November 15, 1961, and warned them. They didn’t act fast enough. By November 27, Germany pulled the drug. The UK followed on December 2. But the U.S. never approved it for sale. Why? Because a single FDA reviewer, Frances Oldham Kelsey, refused to sign off. She asked for more data. She doubted the safety claims. Her skepticism saved thousands of American babies.The Teratogenic Window

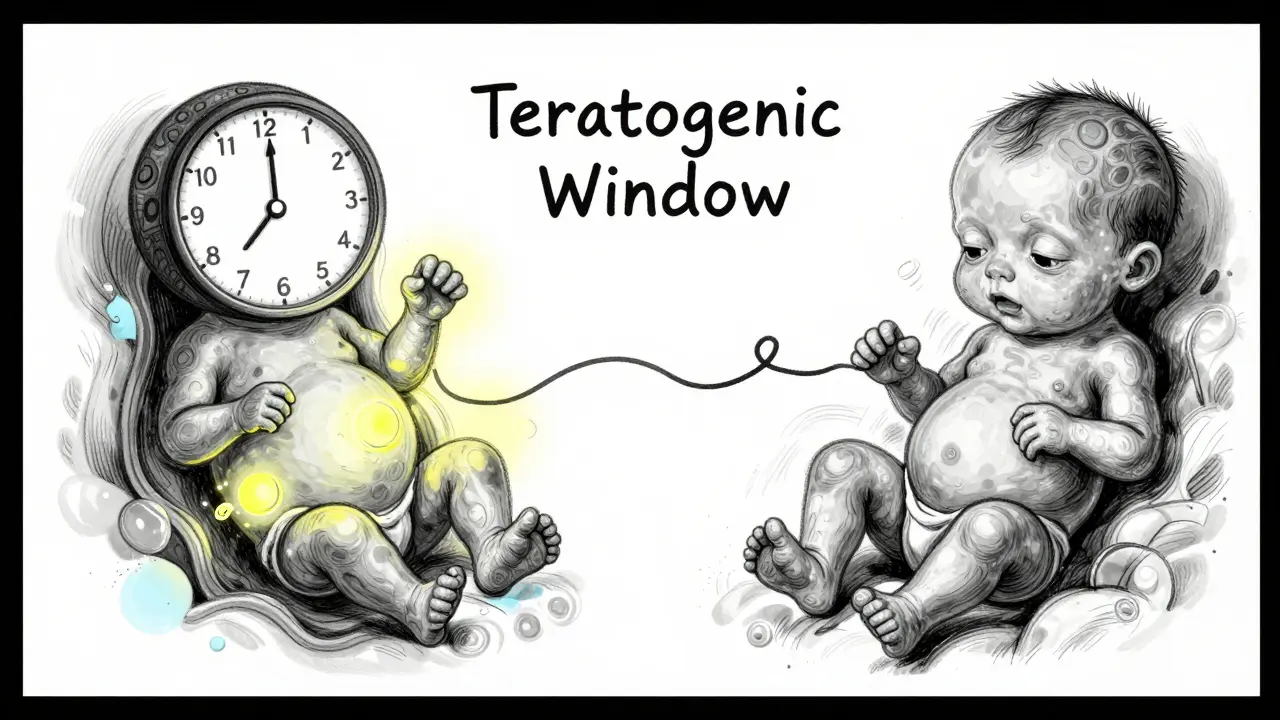

The real horror wasn’t that thalidomide caused birth defects-it was that it only did so in a tiny window. Between 34 and 49 days after the last menstrual period, a developing embryo’s limbs, ears, and organs were forming. One dose, taken during those 15 days, could destroy a baby’s arms or legs. After that, it was safe. Before that, the embryo wasn’t developed enough to be harmed. That’s why it took so long to connect the dots. Doctors thought the defects were random. Genetic. Environmental. Not drug-related. Even today, we don’t fully understand why some babies were affected and others weren’t. But we know the timing. That’s why, in modern medicine, we don’t just ask if a drug is safe for adults-we ask: What happens if a woman takes this while pregnant?The Molecular Breakthrough

For over 50 years, scientists didn’t know how thalidomide caused these defects. In 2018, researchers finally found the answer. Thalidomide binds to a protein called cereblon. That protein normally helps control how genes turn on and off during development. When thalidomide grabs it, the protein starts breaking down key transcription factors-ones that tell the body how to grow arms and legs. Without them, limbs don’t form. The same mechanism is why thalidomide works against cancer: it disrupts the growth signals in tumor cells. This discovery didn’t make thalidomide less dangerous. It made it more understandable. And that’s what changed everything.

From Tragedy to Treatment

Thalidomide didn’t disappear after the 1960s. In 1964, a doctor in Peru named Jacob Sheskin gave it to a leprosy patient with painful skin sores-and the sores vanished. The drug had anti-inflammatory power. Decades later, in the 1980s, scientists realized it blocked new blood vessel growth-something tumors need to survive. By 1998, the FDA approved it for leprosy complications. In 2006, it got the green light for multiple myeloma, a blood cancer. In clinical trials, patients on thalidomide lived longer. More than 40% survived without disease progression at three years, compared to 23% without it. But here’s the catch: up to 60% of patients had nerve damage-numbness, tingling, pain. That’s why it’s never given casually. It’s only used under strict rules.The System That Keeps Babies Safe

Today, thalidomide is one of the most tightly controlled drugs in the world. In the U.S., Canada, Australia, and Europe, it’s only available through the STEPS program-System for Thalidomide Education and Prescribing Safety. Here’s what it requires:- Two negative pregnancy tests before starting

- Two forms of birth control for women of childbearing age

- Monthly pregnancy tests during treatment

- Signed consent forms acknowledging the risk

- No refills without a new prescription

- Men must use condoms-even if they’ve had a vasectomy-because the drug can be in semen

How the World Changed

Before thalidomide, drug companies didn’t need to prove a drug was safe for pregnancy. After? Everything changed. In 1962, the U.S. passed the Kefauver-Harris Amendments. Now, every new drug had to prove both safety and effectiveness. Animal testing for birth defects became mandatory. The UK created the Committee on the Safety of Medicines. Other countries followed. Today, every drug label includes a pregnancy category-whether it’s safe, risky, or unknown. That system? It exists because of thalidomide. The Science Museum in London has a permanent exhibit on it. Medical schools teach it in the first week of pharmacology. It’s not just history-it’s a warning that’s still alive.What We Still Don’t Know

We still don’t know why some women who took thalidomide had healthy babies. Was it genetics? Dose? Timing? We also don’t know how many children were affected but never counted-stillborns, miscarriages, or babies who died before diagnosis. The official number is 10,000. Some experts believe it’s closer to 20,000. And we still don’t have a way to predict who’s at highest risk. That’s why the only safe answer remains: avoid thalidomide during pregnancy-period.What This Means for You

If you’re pregnant, breastfeeding, or planning to be, here’s what you need to know:- Never take any new medication without asking your doctor if it’s safe in pregnancy.

- Some drugs that seem harmless-like certain acne creams, antidepressants, or even herbal supplements-can harm a developing baby.

- Just because a drug is sold over the counter doesn’t mean it’s safe during pregnancy.

- Always check the label. Look for pregnancy warnings. If you’re unsure, call your pharmacist.

- Keep a list of everything you’re taking-even vitamins and teas.

Why This Matters Beyond Thalidomide

Thalidomide isn’t the only teratogenic drug. Isotretinoin (Accutane) causes severe birth defects. Certain antiseizure medications like valproate carry high risks. Even some antibiotics and blood pressure drugs can be dangerous. The lesson isn’t just about one drug. It’s about how we treat medicine as a whole. Just because something works for adults doesn’t mean it’s safe for a fetus. Just because a drug is old doesn’t mean it’s safe. Just because it’s prescribed doesn’t mean it’s risk-free. We owe the survivors of thalidomide more than sympathy. We owe them vigilance. We owe them questions. We owe them the courage to say: “Is this really safe?”Today, thalidomide saves lives. But it still carries the weight of thousands of lost ones. That’s why its story isn’t over. It’s a reminder-every pill, every prescription, every decision matters.

Milla Masliy

13 January, 2026 . 16:02 PM

Wow. I never realized how much one person’s skepticism could change the course of medical history. Frances Kelsey didn’t just do her job-she saved generations. It’s wild to think that if she’d signed off, we’d be looking at a completely different landscape for prenatal care today. I’m honestly in awe of her quiet courage.

Also, the STEPS program? That’s the gold standard. No excuses. No gray areas. If we treated every high-risk drug like this, we’d avoid so many tragedies.

And honestly? We still don’t talk enough about how many women were never counted. The 10,000 number feels like a cold statistic. Behind it are families who lost babies they never got to hold.

I’m printing this out and showing it to my OB-GYN next visit. Everyone needs to know this story.

Damario Brown

14 January, 2026 . 00:32 AM

lol so thalidomide was bad but now its used for cancer? so what now we just say ‘oops’ and move on? this is why i dont trust doctors. one day its poison next day its magic. also why do men need condoms if they got a vasectomy? that’s just a scam to sell more condoms. also who the hell thought it was safe for preggo women? dumbasses.

also frances kelsey? yeah sure she was cool but if she didnt do it someone else would’ve. dont make her a hero. just do your job. also why is this even a thing on reddit? its 2025.

sam abas

15 January, 2026 . 21:20 PM

Let’s be real here-the entire narrative around thalidomide is a myth perpetuated by medical institutions to justify increased regulatory control and funding. The ‘10,000 victims’ figure is inflated. Many of those birth defects were likely due to poor nutrition, alcohol use, or genetic anomalies common in post-war Europe. The fact that the drug was pulled in some countries but not others? That’s just confirmation bias. The real story is that the medical establishment needed a scapegoat to justify its own incompetence in pharmacovigilance. And now? We have a multi-billion-dollar industry built on fear of pregnancy and pharmaceutical liability. The real tragedy? We’ve lost the ability to trust any drug, even ones that could help people, because of overcorrection.

Also, the cereblon mechanism? Fascinating, but it doesn’t explain why some women had healthy babies. That’s the part they don’t want you to ask about.

And the STEPS program? It’s not safety-it’s control. You can’t take a pill without jumping through 17 hoops. That’s not medicine. That’s surveillance.

Clay .Haeber

17 January, 2026 . 13:03 PM

Oh wow, look who’s got a PhD in ‘I Read One Article on Wikipedia and Now I’m a Bioethicist.’

Let me get this straight-because one woman said ‘no’ to a drug, we now have a whole system where men have to wear condoms even after vasectomies? That’s not safety. That’s performative bureaucracy dressed up as compassion. And don’t even get me started on the ‘moral panic’ around pregnancy and drugs. Next they’ll ban caffeine because ‘some’ women drank it and had a baby with a cleft palate. (Spoiler: correlation ≠ causation, but hey, let’s sell more pregnancy tests.)

Also, the fact that we still use thalidomide for cancer? That’s like using a flamethrower to light a candle. But hey, if it works, right? Just don’t ask how many people it burned on the way to the light.

And Frances Kelsey? Cute. But she didn’t ‘save’ anyone. She just happened to be the one who said ‘wait’ while everyone else was drunk on optimism. That’s not heroism. That’s luck.

Also, why is this on Reddit? We’re not in 1962 anymore. We have AI. We have gene editing. We have better drugs. Why are we still crying over a 70-year-old mistake like it’s the end of the world?

Priyanka Kumari

18 January, 2026 . 22:21 PM

This is such an important story-not just for medicine, but for humanity. I’m from India, and I’ve seen how easily people trust doctors without asking questions. We need to teach this in schools. Not just as history, but as a mindset: ask, double-check, don’t assume.

And I love how the STEPS program treats everyone equally-men, women, cis, trans. It doesn’t matter who you are. If you’re near a pregnancy risk, you follow the rules. That’s justice.

Also, the part about the 15-day window? It’s terrifying, but it’s also beautiful. Science finally figured out why. That’s the power of persistence.

Thank you for writing this. I’m sharing it with my sister who’s trying to conceive. She needs to hear this.

Avneet Singh

20 January, 2026 . 18:47 PM

Thalidomide’s reclassification as a ‘controlled cancer therapy’ is a textbook example of pharmaceutical rebranding masquerading as scientific progress. The cereblon mechanism? Overhyped. The real issue is that the FDA’s approval process remains fundamentally flawed-relying on animal models that don’t replicate human embryogenesis accurately. We’re still using 1960s-era teratogenicity screening protocols, just with fancier labels.

And the STEPS program? A performative compliance theater. It doesn’t prevent misuse-it just shifts liability. You can’t regulate human behavior with paperwork. Especially not in a world where online pharmacies ship pills in 48 hours.

Also, calling it a ‘tragedy’ is emotionally manipulative. It’s a pharmacological failure, not a moral parable. We need data-driven policy, not feel-good museum exhibits.

Nelly Oruko

21 January, 2026 . 10:22 AM

It’s not about the drug. It’s about the silence.

Doctors didn’t ask. Women didn’t question. Scientists didn’t look. And the companies? They didn’t care.

Now we have systems. But systems don’t think. People do.

Ask. Always ask.

Even if it feels silly.

Even if they roll their eyes.

Even if it’s just a vitamin.

One question, one moment of doubt-could save a life.

That’s the real lesson.

vishnu priyanka

22 January, 2026 . 05:35 AM

Man, this hits different. I’m from India, and we’ve got a whole culture of ‘doctor knows best’-no questions, just take the pill. My cousin took some herbal ‘pregnancy tea’ last year and ended up in the hospital. No one told her it could be dangerous.

This story? It’s not just about thalidomide. It’s about power. Who gets to decide what’s safe? And why do we wait for disaster before we listen?

Also, the part about men needing condoms? That’s wild. But also… kind of fair? If the drug’s in semen, then yeah, it’s not just a ‘woman’s problem.’

Shoutout to Frances Kelsey. She didn’t have a spotlight. She just did the right thing. That’s the kind of person we need more of.

Angel Tiestos lopez

23 January, 2026 . 15:12 PM

frances kelsey is the real MVP 🙌

also the cereblon thing? mind blown 🤯

and the STEPS program? yessssss this is how you do it. no cap.

why are we still letting people take random meds during pregnancy like it’s a game of russian roulette? 😭

also… why is this not on every med school syllabus on day one? like… come on.

also… anyone else think we’re gonna look back at 2025 and be like ‘wait… we let people take Xanax while pregnant??’ 😅

thank you for this. i’m sharing this with my whole family.

Robin Williams

24 January, 2026 . 08:03 AM

Every time I think about how one drug, one decision, one moment of doubt changed the entire future of medicine… I get chills.

We don’t just owe the survivors of thalidomide their story. We owe them our vigilance.

It’s not about fear. It’s about responsibility.

Every pill you take, every prescription you fill, every ‘it’s just a vitamin’ you dismiss-

it’s not just for you.

It’s for the next generation.

And if we forget that?

We’re not just repeating history.

We’re betraying it.