For people with recent African ancestry, kidney disease doesn’t just happen randomly. A hidden genetic factor - APOL1 - plays a major role in why rates of kidney failure are 3 to 4 times higher than in other populations. This isn’t about race. It’s about ancestry, evolution, and biology. And understanding it changes everything about how we prevent, test for, and treat kidney disease.

What Is APOL1, and Why Does It Matter?

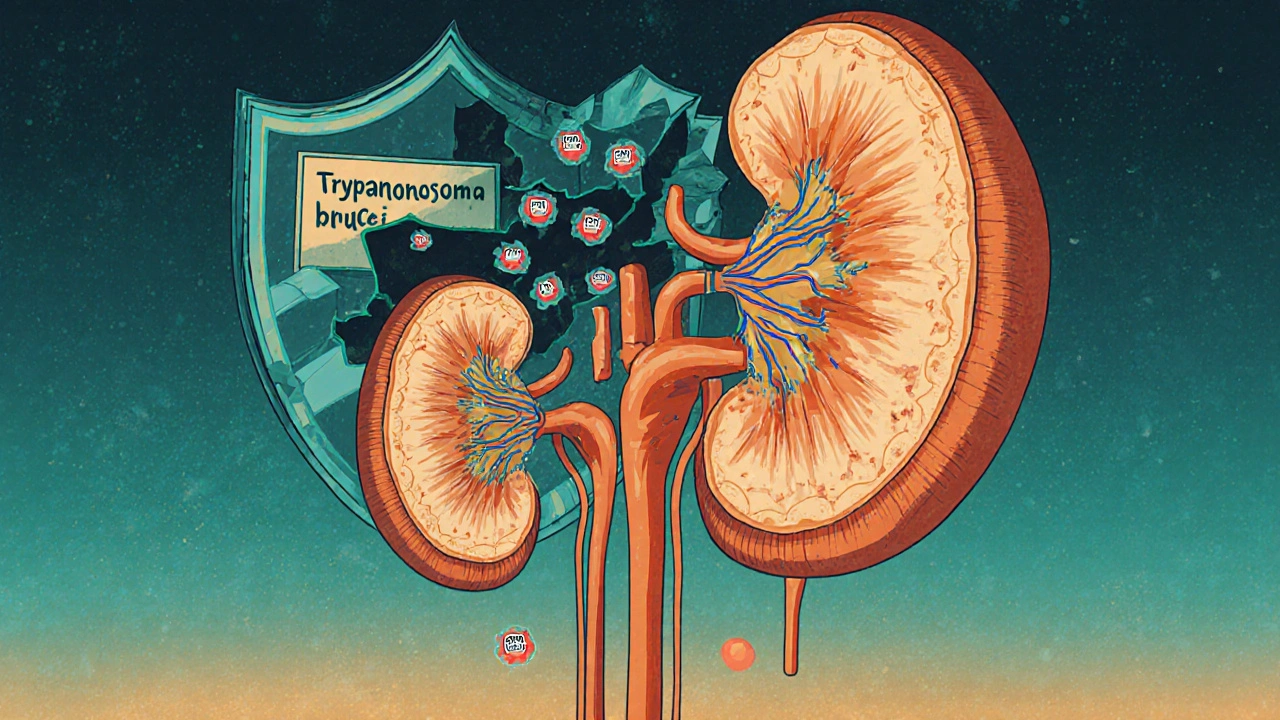

APOL1 is a gene that makes a protein in your blood. Its original job? To protect you from African sleeping sickness. Thousands of years ago, in West and Central Africa, people who carried certain versions of this gene - called G1 and G2 - were more likely to survive infection by the Trypanosoma brucei parasite. Those who survived passed the gene on. Over generations, these variants became common in populations from that region.

But here’s the twist: the same change that saved lives from a deadly parasite now increases the risk of kidney damage. The APOL1 protein, in its mutated form, starts attacking the kidney’s filtering cells. It’s like a security system that’s too aggressive - it fights off invaders but ends up harming your own house.

These variants are almost never found in people of European, Asian, or Indigenous American ancestry. But in people with recent African ancestry - including African Americans, Afro-Caribbeans, and Black Africans - about 30% carry at least one copy. About 13% carry two copies. That’s the high-risk group.

How Do You Get High-Risk APOL1?

You don’t get it from your environment. You inherit it. Like eye color or blood type. But unlike most inherited diseases, APOL1 doesn’t follow a simple dominant pattern. You need two bad copies to be at high risk.

That means:

- G1/G1 (two copies of the G1 variant)

- G2/G2 (two copies of the G2 variant)

- G1/G2 (one of each - called compound heterozygous)

Only these combinations raise your risk significantly. If you have just one copy, you’re a carrier - you won’t develop APOL1-related kidney disease. But you can pass it on to your kids.

That’s why it’s called a recessive trait. And why most people with the high-risk genotype - around 80% - never develop kidney disease. Something else has to trigger it. That’s the "second hit." And that’s where things get complicated.

What Triggers Kidney Damage in High-Risk People?

Having two bad copies of APOL1 doesn’t mean you’ll get kidney failure. It means you’re sitting on a ticking clock. Something has to set it off.

Known triggers include:

- HIV infection - especially in the past, before antiviral treatments improved. HIV-associated nephropathy (HIVAN) was once common in Black patients with APOL1 risk variants. Today, it’s rarer, but still linked.

- High blood pressure - especially if it’s uncontrolled. Many people with APOL1 risk are told they have "hypertensive kidney disease," but the real driver may be the gene.

- Obesity and metabolic stress

- Other viral infections

- Chronic inflammation

One study found that nearly half of all end-stage kidney disease cases in Black patients with HIV were due to APOL1. Another found that among Black patients with non-diabetic kidney disease, about half had the high-risk genotype. That’s not coincidence. That’s causation.

What Kidney Diseases Are Linked to APOL1?

APOL1 doesn’t cause one single disease. It causes a group of rare but aggressive kidney conditions:

- Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) - scarring in the kidney’s filtering units. This is the most common.

- Collapsing glomerulopathy - a severe form of FSGS where the filters literally collapse. Often seen in HIV patients with APOL1 risk.

- Arterionephrosclerosis - kidney damage from high blood pressure, but worsened by APOL1.

These conditions progress faster than typical kidney disease. They respond poorly to standard treatments like steroids or ACE inhibitors. And they often lead to kidney failure before age 50.

Why Was This Missed for So Long?

For decades, doctors assumed kidney disease in Black patients was mostly due to high blood pressure or diabetes. Many were told their kidneys were failing because they were "Black." That’s not just wrong - it’s harmful.

Doctors used race-based formulas to estimate kidney function (eGFR). These formulas automatically adjusted results upward for Black patients, assuming they had more muscle mass. But that masked early kidney damage. Many people with APOL1 risk were told their kidneys were fine - when they weren’t.

In 2022, the American Medical Association officially recommended stopping race-based eGFR adjustments. It was a direct result of APOL1 research. You don’t need to guess someone’s race to understand their kidney risk. You just need to test their genes.

Who Should Get Tested for APOL1?

Testing isn’t for everyone. It’s targeted.

Current guidelines from the American Society of Nephrology (2023) recommend testing for:

- People of recent African ancestry with unexplained kidney disease - especially if it’s not caused by diabetes or high blood pressure.

- People with a family history of early kidney failure.

- Living kidney donors of African ancestry - because if they have high-risk APOL1, donating could put their own kidneys at risk.

The test is simple: a blood or saliva sample. Results come back in 7 to 14 days. Cost ranges from $250 to $450 without insurance. Some labs offer financial aid.

But here’s the catch: many doctors still don’t know how to interpret the results. A 2022 survey found that 78% of nephrologists felt undertrained in APOL1 counseling. Patients often walk away thinking they’re doomed. They’re not.

What Does a Positive Result Really Mean?

Let’s be clear: having two APOL1 risk variants doesn’t mean you’ll get kidney disease. It means your risk is higher - maybe 1 in 5 over your lifetime. That’s not 100%. That’s not a death sentence.

Most people with high-risk APOL1 live normal lives. Their kidneys stay healthy. But they need to be vigilant.

Doctors now recommend:

- Annual urine test for albumin (a sign of early kidney damage)

- Regular blood pressure checks - target under 130/80

- Avoiding NSAIDs like ibuprofen (they stress the kidneys)

- Controlling weight and avoiding smoking

- Getting vaccinated against HIV and other viruses

One patient, Emani, found out she had APOL1 risk before any damage occurred. She started monitoring, changed her diet, and stayed active. Five years later, her kidney function is normal. That’s the power of early awareness.

What’s Next? New Treatments on the Horizon

For years, there was nothing to do but wait and monitor. But that’s changing.

Vertex Pharmaceuticals, a major biotech company, has spent over $1.5 billion developing drugs that block the harmful APOL1 protein. Their drug, VX-147, showed a 37% reduction in proteinuria (protein in the urine) in a 2023 trial. That’s a big deal - proteinuria is a sign of kidney damage.

The NIH has launched a 10-year study tracking 5,000 people with high-risk APOL1. They’re trying to predict who will develop disease - and why. That could lead to personalized prevention plans.

And the global market for APOL1 testing is expected to nearly double by 2027. But access remains unequal. Only 12% of low- and middle-income countries offer testing. That’s a moral crisis. This isn’t just a science issue. It’s a justice issue.

Don’t Confuse Ancestry With Race

One of the most important lessons from APOL1 research is this: genetics is not race.

APOL1 risk variants are tied to West African ancestry. Not to skin color. Not to culture. Not to identity. But for years, medicine used race as a shortcut. That led to misdiagnosis, delayed care, and even denial of transplants.

As Dr. Olugbenga Gbadegesin says: "We must be careful not to conflate social constructs of race with genetic ancestry."

Testing for APOL1 removes the guesswork. It replaces stereotypes with science. And that’s progress.

What Can You Do If You’re at Risk?

If you’re of African ancestry and have kidney disease - or a family history of it - ask your doctor about APOL1 testing. Don’t wait until your kidneys are failing.

If you’re healthy but know you carry the risk:

- Get your urine tested every year.

- Keep your blood pressure under control.

- Don’t smoke. Don’t use NSAIDs long-term.

- Stay active. Eat less processed food.

- Find a nephrologist who understands APOL1 - not everyone does.

If you’re considering donating a kidney and have African ancestry - get tested before you donate. Your kidney might be at risk too.

Knowledge isn’t just power. It’s protection.

What percentage of African Americans have high-risk APOL1 genotypes?

About 13% of self-identified African Americans carry two high-risk APOL1 variants (G1/G1, G2/G2, or G1/G2). Among those with non-diabetic kidney disease, that number jumps to about 50%.

Can APOL1-related kidney disease be cured?

There’s no cure yet, but treatments are improving. Managing blood pressure, reducing protein in the urine, and avoiding kidney stressors can slow progression. New drugs like VX-147 are showing promise in reducing kidney damage. Early detection is the best tool we have right now.

Is APOL1 testing covered by insurance?

Coverage varies. Some insurance plans cover it if you have kidney disease or are a living donor candidate. Out-of-pocket costs range from $250 to $450. Organizations like the American Kidney Fund offer financial assistance for qualifying patients.

Do I need to get tested if I have no family history of kidney disease?

Not necessarily - but if you’re of African ancestry and have unexplained kidney problems, high blood pressure, or protein in your urine, testing is strongly recommended. Even without family history, APOL1 can cause disease. Many people don’t know they’re at risk until it’s too late.

Can APOL1 affect kidney transplant outcomes?

Yes. People with high-risk APOL1 who receive a kidney transplant from a donor without the risk variants generally do well. But if the donor has high-risk APOL1, the transplanted kidney is more likely to fail. That’s why living donors of African ancestry are now routinely tested before donation.

Henrik Stacke

21 November, 2025 . 18:56 PM

Finally, someone is talking about this without reducing it to race. APOL1 isn’t about skin color-it’s about West African ancestry, evolutionary trade-offs, and biology. I’m British but have family from Ghana, and learning this changed how I view my own health risks. This isn’t just science-it’s justice.

Thanks for writing this. It’s the kind of clarity medicine desperately needs.

Manjistha Roy

23 November, 2025 . 07:49 AM

This is one of the most important medical articles I’ve read in years. The fact that doctors used race-based eGFR adjustments for decades, masking early kidney damage, is horrifying. And now, with APOL1 testing, we can finally move beyond assumptions to actual genetics. No more guessing. No more bias. Just data.

Every nephrologist should be required to read this. Every patient of African descent should be offered testing. Period.

Jennifer Skolney

24 November, 2025 . 01:59 AM

I’m a Black woman in my 30s with no family history of kidney disease-but I got tested after reading this. Turns out I’m G1/G2. I was terrified at first. But now I’m on a yearly urine test, cutting back on ibuprofen, and watching my BP. It’s not doom-it’s awareness. And awareness is power. 🙌

If you’re African descent and haven’t been tested? Do it. Your future self will thank you.

JD Mette

24 November, 2025 . 12:54 PM

Interesting. I’ve seen a few cases in my practice where patients labeled with hypertensive nephrosclerosis had no history of severe hypertension. The APOL1 connection makes sense. Still, I’m cautious about widespread testing without proper counseling. A positive result can cause unnecessary anxiety if not handled right.

Education is key. Not just for patients, but for providers too.

Olanrewaju Jeph

26 November, 2025 . 07:23 AM

As a Nigerian physician, I can confirm: this is not a new phenomenon. We have seen aggressive FSGS and collapsing glomerulopathy in young adults for decades. Yet, we were told it was "unexplained," or blamed on poor diet, or lack of access to care. The truth was always genetic.

This article is long overdue. We must stop blaming poverty or lifestyle when the root cause is in the DNA. Testing must be accessible in Africa-not just in the U.S. or U.K.

Also, the term "recent African ancestry" is precise. We must use it correctly. Not "Black," not "African," but "recent West African ancestry." Precision saves lives.

Dalton Adams

27 November, 2025 . 01:16 AM

Let’s be real-this is just another example of how lazy medicine used race as a proxy for genetics. I mean, come on. We’ve had whole-genome sequencing for over a decade. Why did it take until 2022 to stop using race-adjusted eGFR? Because the system is broken. And now, with Vertex spending $1.5 billion on VX-147? Classic pharmaceutical exploitation-wait until the disease is common, then sell the cure.

Also, 13% of African Americans have the high-risk genotype? That’s not a minority. That’s a population. And yet, most doctors still don’t know how to interpret it. So we’re still in the Dark Ages. 🤦♂️

And yes, I’ve read the NIH study. And no, I don’t trust their 10-year timeline. We need action now. Not another grant cycle.

Kane Ren

27 November, 2025 . 11:30 AM

Man, this gives me hope. I thought kidney disease was just part of being Black. Like, inevitable. But learning I could prevent it by watching my BP and avoiding NSAIDs? That’s life-changing.

I’m getting tested next week. If I’m high-risk, I’m going to start a support group. Because no one should feel alone with this.

Charmaine Barcelon

27 November, 2025 . 15:17 PM

Ugh. So now we’re blaming genes? What about all the junk food, the soda, the sedentary lifestyles? This is just a way to avoid responsibility. If you’re eating fast food every day and not exercising, don’t blame your DNA. It’s not an excuse.

Also, why are we testing donors? That’s just going to scare people out of donating. We need more kidneys, not less.

And who’s paying for this? Taxpayers? Great. Another expensive test for people who won’t even change their habits.

Karla Morales

29 November, 2025 . 05:35 AM

Let’s analyze this statistically: 30% carry one copy. 13% carry two. 80% of those two-copy carriers never develop disease. So the penetrance is only 20%. That’s low. So why are we panicking?

And yet-biotech companies are already marketing tests. Insurance companies are adjusting premiums. And patients are being told they’re “at risk.”

Is this prevention-or profit?

Also, the fact that only 12% of LMICs offer testing? That’s not a moral crisis. That’s capitalism. 🤷♀️

And the race vs. ancestry debate? Overrated. People don’t care about ancestry. They care about skin color. Stop pretending otherwise.

Javier Rain

29 November, 2025 . 11:30 AM

This is the kind of info that needs to be shouted from the rooftops. I’m a Black man in my 40s. I’ve had high blood pressure for years. I thought it was just stress. Turns out, I might have APOL1. I got tested last month.

Positive. G1/G2.

But I’m not scared. I’m motivated. I’m seeing a nephrologist. I’ve quit ibuprofen. I’m walking every day. I’m eating clean.

This isn’t a death sentence. It’s a wake-up call. And I’m taking it seriously.

If you’re reading this and you’re African descent? Do it. Don’t wait. Your kidneys don’t scream before they fail-they just stop.

Laurie Sala

29 November, 2025 . 22:32 PM

Why is no one talking about the trauma of this? My uncle died of kidney failure at 42. We were told it was "high blood pressure." We never knew it was genetic. We blamed him. We blamed his diet. We blamed him for not taking care of himself.

Now I know it was his genes. And I’m angry. Angry that no one told us. Angry that doctors didn’t know. Angry that we were made to feel guilty.

This isn’t just science. It’s healing.

Lisa Detanna

30 November, 2025 . 23:47 PM

I’m a Black woman who works in public health. I’ve seen too many patients dismissed because their eGFR was "normal" due to race adjustment. I’ve seen people wait years for a transplant because they were labeled "non-compliant"-when their kidneys were failing from APOL1.

This isn’t just about medicine. It’s about dignity.

Thank you for writing this. I’m sharing it with every community center, every church group, every school nurse I know. Knowledge is protection-but only if it reaches people.

Demi-Louise Brown

2 December, 2025 . 23:20 PM

APOL1 testing should be integrated into routine care for adults of African ancestry-especially those over 30. Not as a panic tool, but as a preventive measure. Like cholesterol screening. Like mammograms.

It’s cost-effective in the long run. Preventing one case of ESRD saves over $100,000 in dialysis costs. And it preserves quality of life.

Let’s make this standard. Not optional. Not niche. Standard.

Matthew Mahar

3 December, 2025 . 00:25 AM

wait so if you have one copy you're fine? but if you have two you're kinda screwed? but like 80% of people with two copies never get sick?? so it's like a lottery??

also why is this only in african ancestry? why not in other groups? is it just luck of evolution??

also i think i have this. my grandma had kidney failure. i should get tested. but i'm scared.

anyone else feel like this??

John Mackaill

3 December, 2025 . 06:35 AM

Matthew, you’re not alone. I had the same reaction. I thought, ‘If 80% don’t get sick, why test?’ But then I remembered: the 20% who do? They’re the ones who end up on dialysis by 45. And their kids? They might inherit it too.

Testing isn’t about fear. It’s about control. If you know, you can act. You can monitor. You can avoid NSAIDs. You can keep your BP down.

It’s not a death sentence. It’s a heads-up. And that’s worth a $300 test.

Kane Ren

4 December, 2025 . 00:29 AM

Exactly. I got tested because of this thread. Turns out I’m G1/G2. I didn’t know what to do. So I called my local kidney foundation. They hooked me up with a free nurse navigator. She helped me understand my results, set up annual tests, and even found a doctor who specializes in APOL1.

You’re not alone. Reach out. Someone’s got your back.