When a drug leaves the lab and enters the market, its safety doesn’t just depend on how well it was made. It depends on how well it holds up over time. That’s where stability testing comes in. This isn’t optional. It’s a legal requirement. If a pill, injection, or inhaler degrades before the expiration date, it could lose potency-or worse, become harmful. Regulatory agencies like the FDA and EMA don’t just ask for stability data; they demand it under strict, globally recognized conditions.

Why Temperature and Time Matter

Drugs don’t stay stable in a box. Heat, moisture, and time change their chemistry. A tablet might absorb moisture and crumble. A liquid might separate. A biologic might clump. These changes aren’t always visible. That’s why stability testing uses controlled environments to simulate real-world storage and shipping conditions over months or years.

The foundation of this process is ICH Q1A(R2), a guideline developed in the 1990s by regulators from the U.S., Europe, and Japan. It’s still the global standard today. It doesn’t just say “test your drug.” It tells you exactly where, how long, and under what conditions.

Long-Term Testing: The Real-World Clock

Long-term testing is the backbone of shelf life determination. It’s where you store your product under conditions that match where it will actually be sold. The ICH Q1A(R2) standard gives two main options:

- 25°C ± 2°C with 60% RH ± 5% RH

- 30°C ± 2°C with 65% RH ± 5% RH

Which one you pick depends on your target market. If you’re selling in Europe or North America, 25°C/60% RH is typical. If you’re targeting tropical regions like Southeast Asia or parts of Africa, you’ll need to use 30°C/65% RH. These aren’t suggestions. They’re requirements.

At minimum, you need 12 months of data before you can submit your drug for approval in the U.S. The EMA allows 6 months if you’re using Option B, but 12 months is still the gold standard for global submissions. Testing doesn’t stop at 12 months-it continues through 24, 36, even 48 months to confirm the product stays stable beyond its labeled shelf life.

Testing intervals are precise: 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, 24, and 36 months. Early time points (like 3 and 6 months) catch early degradation. Later points confirm long-term stability. Missing a single time point can invalidate the entire study.

Accelerated Testing: The Speed Trap

Waiting 12 months to get data isn’t practical for development. That’s why accelerated testing exists. It’s a forced stress test designed to predict long-term behavior in a fraction of the time.

The global standard is simple: 40°C ± 2°C with 75% RH ± 5% RH for 6 months. This isn’t arbitrary. It’s based on decades of data showing that most small-molecule drugs degrade predictably under these conditions. If a drug passes this test without significant change, regulators assume it will be stable at room temperature for at least two years.

But here’s the catch: it doesn’t work for everything. Hygroscopic drugs (those that soak up moisture) often fail here even if they’re fine in real life. Biologics, like monoclonal antibodies, can denature irreversibly at 40°C. That’s why accelerated testing is a warning sign-not a guarantee.

When a drug shows “significant change” during accelerated testing, you must run intermediate testing. That means moving the product to 30°C ± 2°C with 65% RH for another 6 months. This bridges the gap between accelerated and long-term conditions. If the drug holds up here, it’s a strong signal that your long-term data will be valid.

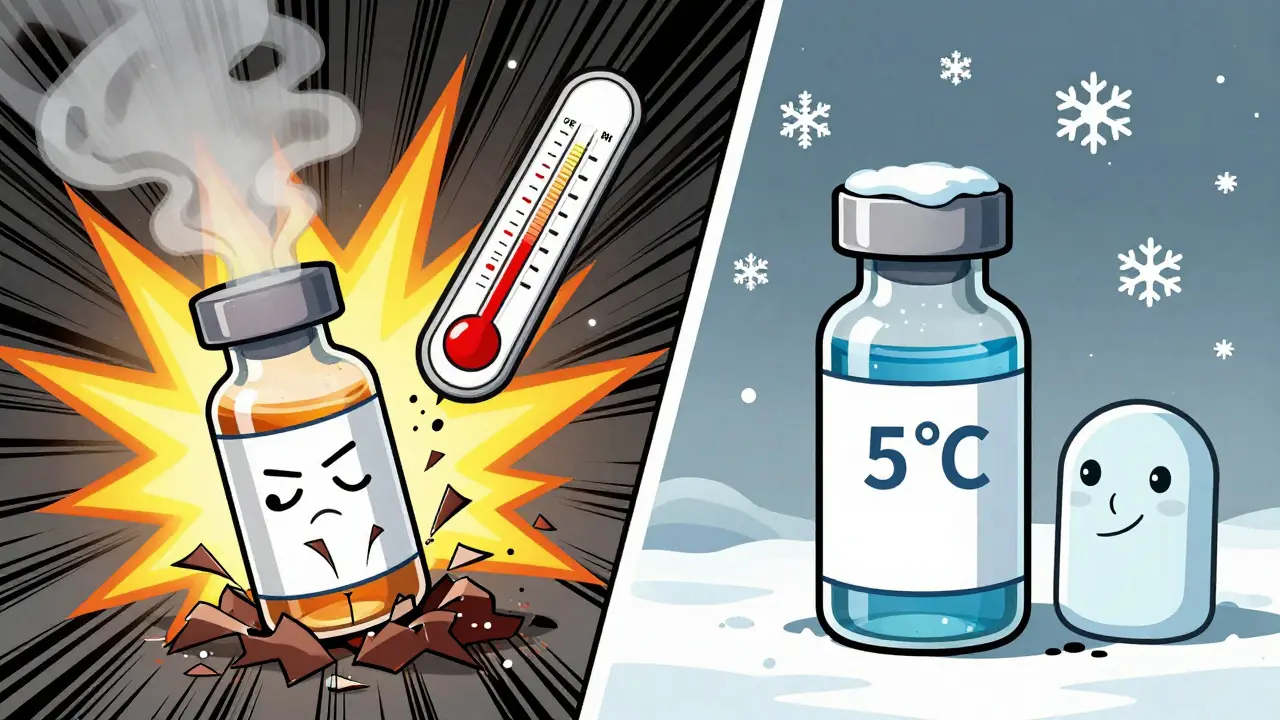

Refrigerated and Frozen Products: Different Rules

Not all drugs are stored at room temperature. Vaccines, insulin, and many biologics require refrigeration-or even freezing. Their stability rules are different.

- Long-term: 5°C ± 3°C for 12 months

- Accelerated: 25°C ± 2°C with 60% RH ± 5% RH for 6 months

Notice that the accelerated condition isn’t 40°C. That’s because freezing and thawing cycles, not heat, are the real threat. Testing at 25°C simulates accidental warm-up during transport. A product that survives 6 months at 25°C is likely safe if it briefly warms up in a delivery truck.

WHO’s guidelines add another layer: for products meant for Zone IVb (hot and humid), even refrigerated products need special attention. A vaccine that’s fine in a fridge in the U.S. might degrade faster in a clinic in Nigeria without proper cold chain support.

What Counts as “Significant Change”?

This is where things get messy. ICH Q1A(R2) defines “significant change” as:

- A 5% change in assay (potency)

- A 10% change in degradation products

- Failure to meet appearance, pH, or dissolution criteria

But here’s the problem: these numbers aren’t always clear-cut. One lab might call a 4.9% drop in potency acceptable. Another might reject it. A Pfizer quality analyst once described how a 4.8% assay result was flagged for rejection-even though it was statistically insignificant-because regulators interpreted it as crossing the line.

There’s no universal calibration. Companies often end up arguing with regulators over what “significant” really means. That’s why many now run extra tests: dissolution profiles, particle size, moisture content, even spectroscopy. The more data you have, the better your defense.

Real-World Challenges

Even with perfect protocols, things go wrong.

Temperature excursions happen. A lab’s stability chamber might lose power for 3 hours. A shipment might sit in a warehouse in Texas during a heatwave. According to a 2023 survey of 142 professionals, 78% had experienced at least one temperature excursion exceeding ±2°C during a long-term study. And 32% of those studies were invalidated because of it.

Humidity control is another nightmare. In dry climates, maintaining 60% RH requires humidifiers. In humid ones, it’s about dehumidification. One company reported RH fluctuations of ±8% until they installed dual-loop control systems-which brought it down to ±3%.

And then there’s documentation. A single stability dossier can run 500+ pages. Every temperature log, every test result, every deviation must be archived. If you can’t prove your chamber was calibrated, your data is trash.

The Future: Beyond ICH Q1A(R2)

Despite its age, ICH Q1A(R2) still governs most stability testing. But it’s starting to crack under pressure.

Modern drugs aren’t pills. They’re mRNA vaccines, antibody-drug conjugates, gene therapies. These don’t degrade the way aspirin does. Freeze-thaw cycles, light exposure, even agitation can ruin them. Standard 40°C tests don’t capture that.

The FDA is already testing real-time stability using process analytical technology (PAT). Instead of waiting 12 months, manufacturers might monitor degradation as it happens during production. Early results show this could cut testing time by 30-50%.

Meanwhile, companies are using predictive modeling. By testing at 50°C, 60°C, even 80°C, they can mathematically extrapolate stability at room temperature. One major pharma company reduced its development timeline by 11 months using this method.

But regulators are cautious. The EMA rejected 8 model-based submissions in 2022-2023. They want hard data, not algorithms.

ICH is working on Q1F, a new guideline expected in late 2024 that will address complex products. Until then, companies must walk a tightrope: follow the rules, but prepare for the future.

Bottom Line

Stability testing isn’t about checking a box. It’s about protecting patients. The temperature and time conditions aren’t arbitrary-they’re based on real-world data, decades of failures, and hard lessons learned. Whether you’re developing a generic tablet or a cutting-edge biologic, ignoring these conditions risks more than regulatory rejection. It risks patient safety.

Follow the ICH standards. Document everything. Test beyond the minimum. And never assume your product will stay stable just because it worked in the lab.