When a child snores loudly, stops breathing for a few seconds during sleep, or wakes up gasping, it’s not just noise-it’s a sign something serious might be happening. Pediatric obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) affects 1 to 5% of all children, mostly between ages 2 and 6, when their tonsils and adenoids are largest relative to their airways. Left untreated, this isn’t just about poor sleep. It can lead to learning problems, behavioral issues, slow growth, and even heart strain over time.

Why Tonsils and Adenoids Are the Main Culprits

In kids, enlarged tonsils and adenoids are the #1 cause of obstructive sleep apnea. These are soft tissues at the back of the throat and nose that help fight infections. But when they grow too big-often after repeated colds or allergies-they block the airway while the child sleeps. Unlike adults, where obesity is the main issue, kids usually have OSA because their airways are physically squeezed shut by swollen tissue.Dr. David Gozal, a leading pediatric sleep expert, found that removing just one (tonsils OR adenoids) often isn’t enough. Both need to come out because OSA isn’t caused by one swollen tissue-it’s the combined blockage. That’s why adenotonsillectomy (removing both) is the standard first step in treatment.

Adenotonsillectomy: The First-Line Treatment

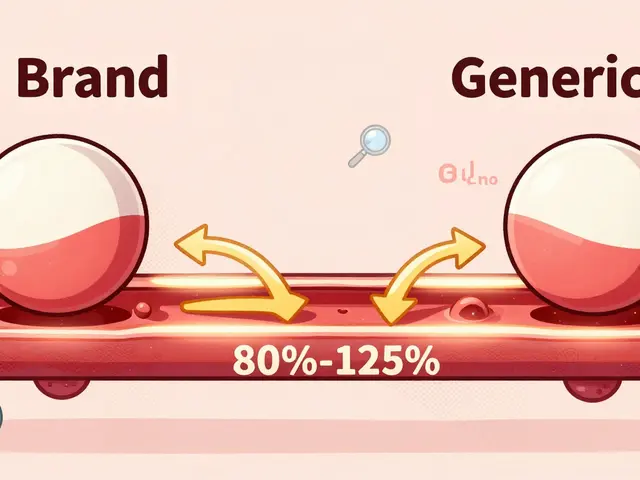

The American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Thoracic Society both agree: for otherwise healthy kids with enlarged tonsils and adenoids, surgery is the best starting point. Success rates? Between 70% and 80% in kids without other health issues.The procedure is done under general anesthesia. Most kids go home the same day. Recovery takes about a week to two, with soft foods and rest required. Pain is common but manageable. Some hospitals now offer partial tonsillectomy, where only part of the tonsil is removed. This reduces bleeding, pain, and recovery time by up to 30%-though it’s not available everywhere.

But surgery doesn’t always fix everything. Studies show 17% to 73% of children still have sleep apnea after surgery, especially if they’re overweight, have craniofacial differences, or suffer from neuromuscular conditions. That’s why follow-up sleep studies are critical. The American Thoracic Society recommends another sleep test 2 to 3 months after surgery to make sure the airway is truly open.

What If Surgery Doesn’t Work-or Isn’t an Option?

Not every child is a good candidate for surgery. Kids with Down syndrome, cerebral palsy, or severe obesity often have airway problems that aren’t solved by removing tonsils alone. That’s where CPAP comes in.CPAP (Continuous Positive Airway Pressure) uses a small machine connected to a mask worn over the nose or face. It blows gentle, steady air into the throat to keep the airway open all night. For kids, pressure settings are usually between 5 and 12 cm H₂O, carefully adjusted during a sleep study to find the perfect level.

CPAP is highly effective-85% to 95% of kids see their breathing interruptions disappear when they use it consistently. But here’s the catch: kids hate wearing masks. About 30% to 50% of children struggle to use CPAP every night. Why? The mask feels strange, it’s uncomfortable, they get claustrophobic, or it leaks air and wakes them up.

Success with CPAP depends on fitting. Pediatric masks are smaller, softer, and come in different styles-nasal pillows, full-face, or hybrid. Many families need 2 to 8 weeks to get used to it. And because kids grow fast, masks must be checked and replaced every 6 to 12 months. Mayo Clinic experts say proper fitting makes all the difference. A well-fitted mask doesn’t just work better-it’s easier to live with.

Other Treatments: When Surgery and CPAP Aren’t Enough

Some kids need more than surgery or CPAP. For those with narrow palates, orthodontists can use rapid maxillary expansion. This device gently widens the upper jaw over 6 to 12 months, creating more space for the tongue and airway. Success rates? Around 60% to 70% in kids with true palate narrowing.For milder cases, doctors sometimes prescribe inhaled corticosteroids-nasal sprays like fluticasone. These reduce inflammation in the adenoids and tonsils. Studies show 30% to 50% improvement in breathing after 3 to 6 months of daily use. It’s not a cure, but it can delay or even avoid surgery in some cases.

Newer options are emerging. Leukotriene blockers like montelukast (usually used for asthma) are being tested to shrink lymphoid tissue. Early results show promise, but it takes months to see results. Another option-hypoglossal nerve stimulation-is now FDA-approved for select pediatric cases. It’s a tiny implant that nudges the tongue forward during sleep to prevent blockage. But it’s only used in rare, complex cases where other treatments have failed.

How Do Doctors Know It’s Sleep Apnea?

You can’t diagnose this just by watching your child sleep. The gold standard is a polysomnography-an overnight sleep study. During this test, sensors monitor:- Brain waves (to track sleep stages)

- Heart rhythm

- Oxygen levels in the blood

- Carbon dioxide levels

- Chest and belly movement (to see if breathing efforts are blocked)

- Muscle activity

- Airflow through the nose and mouth

A child with severe OSA might stop breathing 15 to 30 times per hour. That’s not snoring-that’s a medical emergency in the making.

What Happens If You Wait?

Many parents think, “My child will grow out of it.” But untreated pediatric OSA doesn’t just go away. Chronic sleep fragmentation and low oxygen levels affect brain development. Kids may struggle with attention, memory, and school performance. They’re more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD. Their growth hormone is suppressed, leading to slower height gain. And over time, the heart has to work harder, raising the risk of high blood pressure and heart problems later in life.There’s no safe “wait and see” period for moderate to severe OSA. If your child snores, breathes through their mouth, has frequent night sweats, or seems tired during the day despite sleeping enough-it’s time to talk to a pediatric sleep specialist.

Choosing the Right Path: Surgery, CPAP, or Something Else?

There’s no one-size-fits-all answer. Here’s how most doctors decide:| Child’s Profile | Best First Treatment | Why? |

|---|---|---|

| Healthy, ages 2-6, large tonsils/adenoids | Adenotonsillectomy | 80% success rate; fixes root cause |

| Obese child (BMI >95th percentile) | CPAP | Surgery often fails; CPAP works better |

| Child with Down syndrome or cerebral palsy | CPAP | Airway issues are neurological, not just anatomical |

| Mild OSA, no surgery candidate | Inhaled steroids or montelukast | Non-invasive; 30-50% improvement |

| Narrow palate, mouth breathing | Rapid maxillary expansion | Addresses structural issue long-term |

| OSA returned after surgery | CPAP or DISE-guided surgery | Find hidden blockages; CPAP fills the gap |

Doctors at Yale and UChicago now use drug-induced sleep endoscopy (DISE) to see exactly where the airway collapses during natural sleep. This helps plan surgery more precisely-especially for kids who didn’t improve after tonsil removal.

What Parents Can Do

If your child is diagnosed with sleep apnea:- Don’t delay treatment. The brain develops fastest between ages 2 and 6.

- Ask about partial tonsillectomy if surgery is recommended-it’s less painful.

- If CPAP is suggested, work with a pediatric sleep tech. Don’t give up after a bad week.

- Keep a sleep diary: note snoring, pauses, restlessness, daytime tiredness.

- Watch for signs of recurrence: snoring returns, bedwetting comes back, school performance drops.

Most kids who get the right treatment-whether surgery, CPAP, or a combination-go on to sleep normally, learn better, and grow stronger. The key is acting early, staying involved, and not accepting “it’s just a phase.”

Is sleep apnea common in kids?

Yes. About 1 to 5% of children have obstructive sleep apnea, with the highest rates between ages 2 and 6. It’s more common than many parents realize, especially in kids who snore regularly or breathe through their mouths.

Can my child outgrow sleep apnea without treatment?

Sometimes, especially in mild cases tied to temporary swelling from colds or allergies. But if it’s caused by enlarged tonsils or adenoids, it rarely goes away on its own-and waiting can harm brain development, growth, and behavior. Don’t assume it will fix itself.

Does CPAP hurt kids?

The machine doesn’t hurt, but the mask can feel strange at first. Many kids resist it because it’s unfamiliar or feels claustrophobic. With the right mask, gradual introduction, and support from a pediatric sleep team, most kids adjust within a few weeks. Comfort is key-don’t settle for a poor fit.

What are the risks of removing tonsils and adenoids?

The surgery is generally safe, but risks include bleeding (1-3%), infection, and temporary breathing problems right after surgery (0.5-1%). Children with obesity or neuromuscular conditions have higher risks. Partial tonsillectomy reduces bleeding and pain significantly compared to full removal.

How do I know if my child needs a sleep study?

If your child snores louder than normal, stops breathing during sleep, breathes through their mouth, sweats at night, wakes up tired, or shows signs of inattention or hyperactivity during the day, talk to your pediatrician. A sleep study is the only way to confirm sleep apnea.

Can allergies cause sleep apnea in kids?

Allergies don’t directly cause sleep apnea, but they make tonsils and adenoids swell more, worsening the blockage. Treating allergies with nasal steroids or antihistamines can help reduce symptoms, especially in mild cases.

Will my child need CPAP forever?

Not usually. Many children outgrow the need for CPAP as they grow, their airways expand, and their weight stabilizes. Some, especially those with neurological or craniofacial conditions, may need it longer. Regular follow-ups help determine when it’s safe to stop.

Every child’s airway is different. What works for one might not work for another. The goal isn’t just to stop snoring-it’s to give your child the deep, restful sleep their growing body and brain need to thrive.

Sachin Agnihotri

28 November, 2025 . 22:04 PM

Wow, this is such a clear breakdown-I’ve been worrying about my 4-year-old’s snoring for months, and now I finally get why the doc pushed for a sleep study. No more ‘it’s just a phase’ excuses for me.

Diana Askew

29 November, 2025 . 05:55 AM

They’re hiding the truth. Big Pharma doesn’t want you to know that tonsil removal is just a profit scheme. The real cause? 5G towers messing with kids’ airways. I’ve seen it in my neighbor’s kid-stopped snoring after we bought a $200 Faraday canopy. 🤫📡

King Property

30 November, 2025 . 23:50 PM

You people are wasting time with CPAP and steroids. If your kid’s snoring like a chainsaw, you’re a bad parent. Get the surgery done. Period. No excuses. My cousin’s kid had it at 3, slept like an angel by week two. You’re just scared of a little anesthesia.

Yash Hemrajani

2 December, 2025 . 12:01 PM

Oh wow, a 70-80% success rate? That’s cute. I’ve seen 3 kids post-adenotonsillectomy still gasping like fish out of water. And no one talks about how the ‘partial’ tonsillectomy is just a fancy way of saying ‘we didn’t feel like doing the full job.’ 😏

Pawittar Singh

4 December, 2025 . 03:37 AM

Hey everyone-this is HUGE. If your kid snores, don’t wait. My nephew was diagnosed at 5, had the surgery, and now he’s acing kindergarten. He used to be a zombie after school-now he’s running around like a tornado. 💪 It’s not just about sleep-it’s about their whole future. You got this!

Josh Evans

4 December, 2025 . 08:25 AM

Really helpful post. I didn’t realize CPAP success rates were that high. My daughter hates the mask, but we’ve been trying the nasal pillows and she’s slowly getting used to it. Took 3 weeks, but she sleeps better now. Just… patience.

Allison Reed

4 December, 2025 . 14:13 PM

This is an incredibly thorough and compassionate guide. I’m a pediatric nurse, and I see too many parents delay treatment because they’re scared or misinformed. The data here is solid. If your child has symptoms, act. Their developing brain is counting on you.

Jacob Keil

6 December, 2025 . 12:54 PM

CPAP is just a crutch for lazy parents who dont want to fix the real problem. The airway collapses because the body is toxic. Detox with magnesium and raw honey. Also, fluoride in water causes adenoid swelling. Look it up. #Truth

Rosy Wilkens

6 December, 2025 . 17:39 PM

Who authorized this information? The AAP and ATS are controlled by the American Medical Industrial Complex. They profit from surgeries and devices. Did you know that the FDA approved hypoglossal implants after a $200 million lobbying campaign? Don’t be fooled.

Andrea Jones

6 December, 2025 . 18:23 PM

So… you’re saying if my kid breathes through their mouth and snores like a foghorn, I shouldn’t just ‘wait and see’? Huh. I guess that’s why my 6-year-old can’t focus in class. 🤦♀️ Thanks for the kick in the pants. I’m booking the sleep study tomorrow.

Justina Maynard

7 December, 2025 . 20:36 PM

Let me just say-I’ve seen this play out in my own home. My daughter had adenotonsillectomy, then CPAP, then maxillary expansion. It was a three-act tragedy with a happy ending. But oh, the nights I cried over her mask. The fights. The tears. The 3 a.m. struggles. It’s not easy. But it’s worth every second.

Evelyn Salazar Garcia

9 December, 2025 . 17:56 PM

Why are we even talking about this? Kids in America are getting overdiagnosed. Back in my day, we slept on the floor with the window open. Snored? Good. That meant we were alive.

Clay Johnson

11 December, 2025 . 08:05 AM

Truth is, sleep apnea in kids is just the symptom. The disease is modern life. Artificial light. Processed food. Sedentary existence. We’re not treating the root. We’re just patching the leak.

Jermaine Jordan

12 December, 2025 . 03:59 AM

Imagine your child’s brain-growing, learning, dreaming-being starved of oxygen every single night. Not for weeks. Not for months. But for YEARS. This isn’t about snoring. This is about the silent theft of childhood. And we’re letting it happen because it’s ‘just a phase.’

Chetan Chauhan

13 December, 2025 . 15:44 PM

Adenotonsillectomy? Nah. My kid had it done and still snored. Turns out the doc missed the tongue base obstruction. So now I’m convinced they’re all just guessing. Maybe we should just let kids sleep on their stomachs like in the 90s? Works fine.

Phil Thornton

14 December, 2025 . 23:49 PM

My kid had CPAP for a year. We finally weaned him off. He’s 9 now. No snoring. No masks. Just a happy kid who sleeps like a log. The system works-if you stick with it.