Malaria is a vector‑borne infectious disease caused by protozoan parasites of the genus Plasmodium, transmitted primarily through the bite of an Anopheles mosquito. Each year, the World Health Organization estimates over 200million cases and nearly 600000 deaths, the majority among children under five in sub‑Saharan Africa.

Malnutrition is a condition resulting from insufficient intake of calories, protein, or micronutrients, leading to impaired growth, weakened immunity, and higher susceptibility to infection. The Global Nutrition Report notes that more than 45% of children in low‑income regions experience stunting or wasting.

TL;DR

- Malaria infection drains nutrients, heightening the risk of malnutrition.

- Undernourished children have reduced immunity, making malaria episodes more severe.

- Key drivers include poverty, food insecurity, and inadequate vector control.

- Integrated strategies-like insecticide‑treated nets paired with micronutrient supplementation-break the vicious cycle.

- Monitoring both disease incidence and nutritional status is essential for lasting impact.

Why Malaria Fuels Malnutrition

When Malaria parasites invade red blood cells, they trigger fever, anemia, and appetite loss. The fever spikes raise metabolic rates by up to 15%, meaning the body burns more calories while the sick person eats less. In children, repeated bouts can lead to chronic iron deficiency, a primary component of anemia.

Beyond the direct loss of red blood cells, the immune response releases inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin‑6, which suppress appetite and alter gut absorption. Studies from the Kenya Medical Research Institute showed that children with three or more malaria episodes in a year had a 30% higher odds of being underweight compared with malaria‑free peers.

How Malnutrition Amplifies Malaria Risk

Undernourished bodies lack the micronutrients-especially zinc, vitaminA, and iron-needed for a robust immune response. A 2022 WHO briefing highlighted that children with severe acute malnutrition are twice as likely to develop severe malaria, and their recovery takes longer.

Iron deficiency presents a paradox: while low iron can limit parasite replication, it also impairs the host’s ability to produce effective antibodies. Consequently, children with marginal iron stores experience more frequent relapses.

Key Drivers Linking the Two Conditions

- Poverty: Limited resources restrict access to insecticide‑treated nets (ITNs) and nutritious foods.

- Food insecurity: Seasonal crop failures increase reliance on low‑quality staples, lowering protein and micronutrient intake.

- Inadequate health infrastructure: Remote clinics often lack rapid malaria diagnostics and therapeutic feeding programs.

- Environmental factors: Stagnant water habitats boost Anopheles mosquito breeding, while drought‑related malnutrition spikes.

Integrated Intervention Strategies

Breaking the malaria‑malnutrition loop requires combined actions that address both vectors and nutrition gaps.

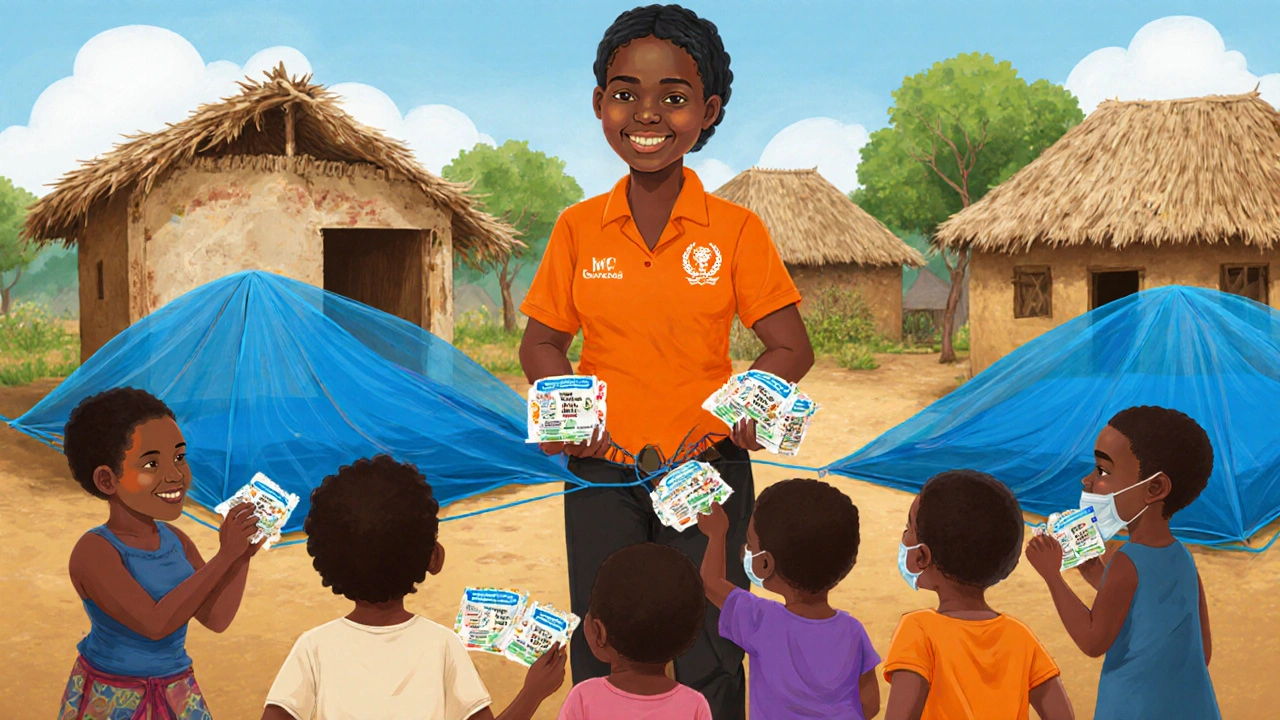

1. Vector control + nutrition supplements

Distributing ITNs alongside micronutrient powders (containing iron, zinc, vitaminA) has shown a 22% reduction in combined incidence of malaria and anemia in Ghana’s northern regions.

2. Seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC) with ready‑to‑use therapeutic foods

In Burkina Faso, pairing SMC for children aged 3‑59 months with lipid‑based nutrient supplements cut severe malaria cases by 35% and lowered stunting rates by 12% over two transmission seasons.

3. Integrated community health worker (CHW) programs

Training CHWs to conduct rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) for malaria, dispense antimalarials, and screen for underweight or wasted children improves early detection. A pilot in Tanzania reported a 40% increase in timely treatment for both conditions.

Comparison Table: Impact Direction

| Aspect | Malaria → Malnutrition | Malnutrition → Malaria |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Mechanism | Hemolysis, fever‑induced appetite loss, cytokine‑mediated gut dysfunction | Weakened cellular immunity, micronutrient deficiencies (iron, zinc, vitaminA) |

| Typical Outcomes | Anemia, weight loss, stunting | Higher parasite density, severe malaria episodes, slower recovery |

| Risk Population | Children <5yrs, pregnant women | Undernourished children, chronically food‑insecure households |

| Effective Countermeasures | ITNs, prompt antimalarial treatment, iron supplementation post‑recovery | Micronutrient supplementation, therapeutic feeding, SMC |

Case Study: The Sahel’s Dual Burden

The Sahel region experiences one of the world’s most intense malaria seasons combined with chronic food shortages. In 2023, the Mali Ministry of Health partnered with the World Health Organization (WHO is the UN agency leading global health policy and disease surveillance, providing technical guidance and funding for malaria‑nutrition programs) to roll out a pilot that merged SMC distribution with fortified blended foods.

Results after two years were striking: malaria incidence dropped by 27% while the prevalence of moderate acute malnutrition fell from 18% to 12% among children aged 6‑23 months. The success hinged on synchronized community meetings that educated families about net use, proper feeding, and signs of severe disease.

Related Concepts and Next Steps

Understanding the malaria‑malnutrition nexus opens doors to explore broader topics such as vector‑borne disease ecology, food security policies, and integrated primary health care models. Readers interested in the epidemiology of other mosquito‑transmitted illnesses (e.g., dengue, Zika) or in climate‑change impacts on disease patterns may find those clusters valuable next.

For practitioners, the next logical move is to audit local health data for overlapping hotspots, then design joint interventions that address both disease prevention and nutritional support. Monitoring tools should capture parasite prevalence, anemia rates, and growth‑monitoring charts side by side.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can malaria cause long‑term stunting in children?

Yes. Repeated malaria infections during the first two years of life can impair linear growth. The inflammation and anemia associated with each episode reduce nutrient absorption, and studies in Uganda have linked three or more infections in the first year to a 0.5‑cm lower average height‑for‑age.

Is iron supplementation safe for children who have malaria?

Iron should be given after the acute malaria episode has been cleared. During active infection, excess iron can fuel parasite replication. WHO recommends a 7‑day antimalarial course before starting iron tablets or fortified foods.

What role do insecticide‑treated nets play in reducing malnutrition?

ITNs lower malaria incidence, which directly cuts the fever‑induced appetite loss and anemia that drive malnutrition. A 2021 meta‑analysis found that households with universal net coverage saw a 15% reduction in child wasting rates.

How does seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC) affect nutrition outcomes?

SMC provides monthly antimalarial doses during peak transmission months. When coupled with lipid‑based nutrient supplements, it not only reduces malaria cases but also improves weight‑for‑height Z‑scores. Trials in Niger showed a 10% drop in acute malnutrition after two SMC cycles.

Are there any community‑level programs that address both issues simultaneously?

Yes. Integrated Community Health Worker (CHW) models that equip workers with rapid malaria tests, antimalarial drugs, and growth‑monitoring tools are gaining traction in Tanzania, Ethiopia, and Nigeria. These programs have demonstrated faster case detection and higher rates of nutritional rehabilitation.

Erin Johnson

27 September, 2025 . 16:16 PM

Oh, the glorious dance of parasites and malnutrition-nothing says “healthy childhood” like a mosquito delivering a double whammy. The way malaria siphons off calories while kids barely get a bite to eat is practically a plot twist in a tragic sitcom. Yet, if we sprinkle a few insecticide‑treated nets and a dash of micronutrient powder, the drama could finally get a happy ending. So, kudos to the integrated programs that actually try to break this vicious cycle.

Rica J

27 September, 2025 . 23:28 PM

yeah the whole thing is kinda messy but ya know the data does show that fevers spike metabolism and loss of appetite makes kids even more vulnerable. getting nets + supplements is a solid move, i think more community health workers could step up the game. also maybe look at local food sources that are iron rich – that’d help too.

Linda Stephenson

28 September, 2025 . 06:40 AM

We have to remember that children aren’t just numbers on a chart; each episode of malaria chips away at their future potential. When a kid loses weight and stamina, school attendance drops, feeding a cycle of poverty. Integrated strategies that pair treatment with nutrition assessments can gently pull families back toward stability.

Sunthar Sinnathamby

28 September, 2025 . 13:52 PM

Listen, Erin-your sarcasm is noted, but the reality is harsher than witty banter. In regions where nets are a luxury, families end up choosing between food and protection. This isn’t a comedy; it’s a daily struggle for survival.

Catherine Mihaljevic

28 September, 2025 . 21:04 PM

All that talk, and the mosquitoes still bite.

Michael AM

29 September, 2025 . 04:16 AM

Totally agree, Rica. The community health workers are the unsung heroes, delivering both tests and supplements. Boosting their training could really shift the odds in kids’ favor.

Rakesh Manchanda

29 September, 2025 . 11:28 AM

The interplay between malaria and malnutrition is far more intricate than a simple cause‑and‑effect relationship. First, the parasite’s lifecycle imposes a metabolic burden that raises basal energy expenditure, often by a measurable margin, while simultaneously curbing appetite through cytokine‑mediated pathways. Second, repeated hemolysis not only depletes iron stores but also triggers compensatory mechanisms that can paradoxically foster iron‑restricted environments, thereby influencing pathogen replication dynamics. Third, the immunological consequences of chronic undernutrition-particularly deficits in zinc, vitamin A, and selenium-diminish both innate and adaptive responses, rendering the host more susceptible to higher parasitemia levels. Fourth, socioeconomic factors such as poverty constrain access to both insecticide‑treated nets and protein‑rich foods, creating a feedback loop that entrenches disease prevalence. Fifth, environmental determinants, including standing water habitats and seasonal agricultural cycles, simultaneously dictate vector density and food security, intertwining the two crises inextricably. Sixth, policy interventions that neglect either vector control or nutritional supplementation tend to produce suboptimal outcomes, as evidenced by pilot studies where isolated distribution of nets failed to curb anemia rates. Seventh, the timing of seasonal malaria chemoprevention aligns closely with periods of crop scarcity, suggesting that synchronized delivery could amplify health gains. Eighth, the role of community health workers as the nexus point for diagnostics, treatment, and nutrition screening cannot be overstated; their presence has been correlated with a measurable decline in both malaria incidence and wasting prevalence. Ninth, cultural practices surrounding food preparation and mosquito avoidance can either mitigate or exacerbate risk, underscoring the need for culturally sensitive education campaigns. Tenth, emerging research into genetically modified mosquitoes offers a tantalizing prospect, yet without addressing the nutritional deficits that predispose children to severe disease, such innovations may achieve only partial success. Eleventh, data from longitudinal cohort studies reveal that children who receive combined interventions exhibit not only lower mortality but also improved cognitive development scores. Twelfth, the cost‑effectiveness analyses consistently favor integrated programmes, demonstrating higher return on investment per DALY averted than siloed approaches. Thirteenth, the global health community must therefore champion holistic models that simultaneously target vector control, therapeutic management, and micronutrient replenishment. Fourteenth, only through such coordinated effort can we hope to break the pernicious cycle that has ensnared millions for generations. Finally, the moral imperative is clear: we must not accept the status quo when a viable, evidence‑backed solution exists.

Erwin-Johannes Huber

29 September, 2025 . 18:40 PM

You’ve nailed the complexity, and the data you cite is compelling. In practice, though, scaling these integrated programmes remains a logistical nightmare, especially in remote districts where supply chains are fragile.

Tim Moore

30 September, 2025 . 01:52 AM

Indeed, the logistical challenges are non‑trivial; however, leveraging existing community health infrastructure-such as village health committees-can streamline distribution channels. Moreover, partnership with local NGOs ensures cultural competency and sustainability, thereby mitigating many of the obstacles you have identified.

Erica Ardali

30 September, 2025 . 09:04 AM

Behold, the tragedy of our age: a microscopic assassin dances upon the very marrow of our children, whilst society feigns ignorance behind polished conference tables. It is a theater of the absurd, where the curtain never falls, and the audience, cloaked in complacency, applauds the very script that condemns the innocent.

Justyne Walsh

30 September, 2025 . 16:16 PM

Ah, the lofty prose, Erica, truly paints a masterpiece-though perhaps the next step is to turn those verses into actionable policy, else we remain stuck in lyrical lament.

Callum Smyth

30 September, 2025 . 23:28 PM

Spot on, Justyne. If only our leaders could match their rhetoric with real funding, we might finally see nets on every door and fortified meals in every school. :)

Selena Justin

1 October, 2025 . 06:40 AM

While the sentiment is appreciated, a rigorous allocation framework is essential to ensure resources are deployed equitably and monitored for efficacy. Such an approach would satisfy both the emotional appeal and the scientific standards required for sustainable impact.

Bernard Lingcod

1 October, 2025 . 13:52 PM

Does anyone have insights on how climate‑change‑induced shifts in mosquito breeding patterns might alter the seasonal timing of malaria outbreaks, and consequently, how we should adjust our nutrition intervention schedules?

Raghav Suri

1 October, 2025 . 21:04 PM

Yo, just thought-if we get those nets out early and drop some ready‑to‑eat nutrient packs, kids might actually stay healthy enough to play soccer again. No big deal, just a thought.