When a hurricane hits, it doesn’t just knock out power and flood homes-it can also stop life-saving drugs from reaching hospitals. In 2017, Hurricane Maria wiped out Puerto Rico’s electrical grid, and for over a year, millions of Americans couldn’t get basic saline IV bags or insulin. That wasn’t an accident. It was the result of a pharmaceutical system built on fragile, centralized production-and now, climate change is making it worse.

Why One Storm Can Break the Medicine Supply

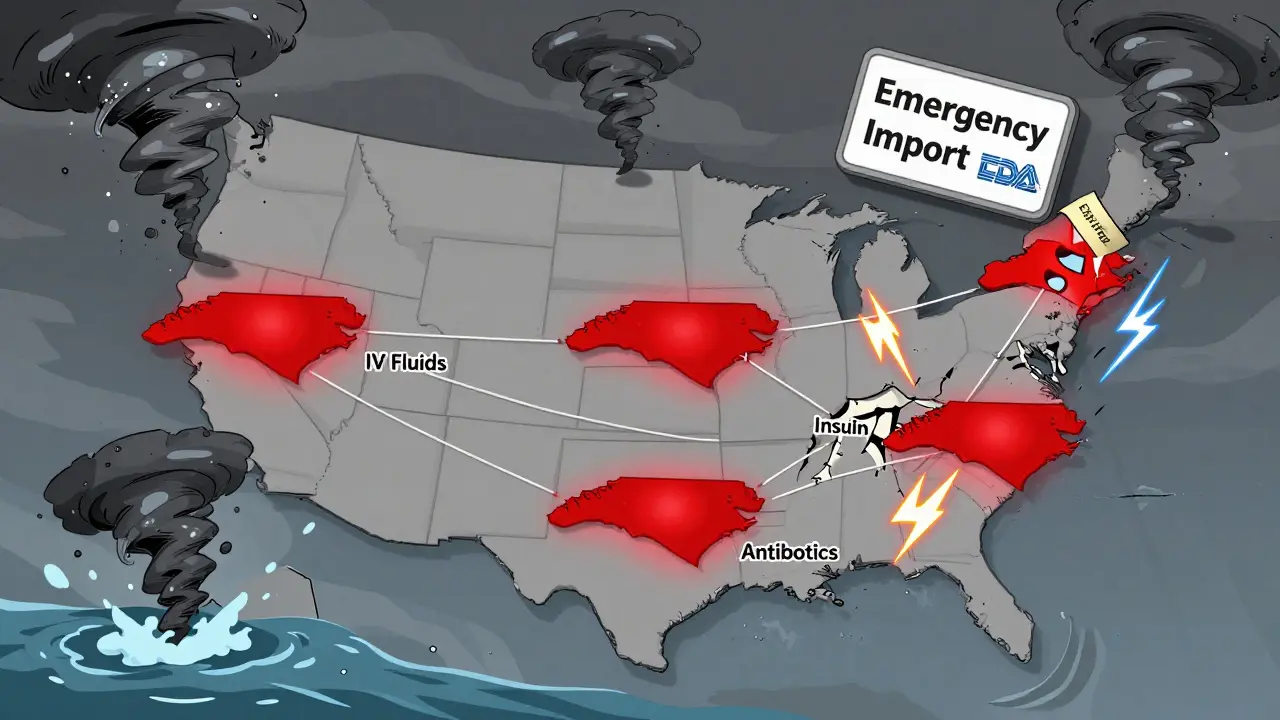

The U.S. doesn’t make most of its drugs across dozens of small factories. It relies on a handful of key locations. Puerto Rico alone used to produce 10% of all FDA-approved drugs and 40% of sterile injectables like saline and antibiotics. After Hurricane Maria, 46 manufacturing sites went dark. The grid took 11 months to fully restore. Insulin shortages lasted 18 months. Hospitals rationed doses. Cancer patients missed treatments. Diabetics ran out of syringes. It wasn’t just Puerto Rico. In 2024, Hurricane Helene slammed into North Carolina, damaging Baxter International’s plant in North Cove. That one facility made 60% of the nation’s IV fluids-1.5 million bags a day. Within 72 hours, hospitals were canceling surgeries. By October, emergency protocols were in place. The FDA warned the shortage could last until mid-2025. These aren’t rare events. Between 2017 and 2024, climate-related disruptions caused 32% of all drug shortages in the U.S., according to the FDA. And 65.7% of pharmaceutical manufacturing facilities sit in counties that have seen at least one major weather disaster since 2018.The Hidden Weak Spots in the System

Most people think drug shortages happen because of money or demand. But the real problem is structure. - **Single points of failure**: 78% of sterile injectable drugs in the U.S. have only one or two manufacturers. If one plant goes down, there’s no backup. - **Geographic concentration**: The same stretch of North Carolina-Marion and Spruce Pine-produces nearly all IV fluids and supplies the quartz used in medical devices. One tornado, one flood, one power line down, and the whole chain snaps. - **No buffer**: The industry runs on “just-in-time” inventory. Factories ship drugs as soon as they’re made. There’s no warehouse stockpile. No safety net. Compare that to how we handle food or fuel. We have reserves. We have regional distribution. We have backup routes. For medicine? Almost none of that exists.Not All Disasters Are the Same

Hurricanes are the biggest threat, causing 47% of climate-related drug shortages. Why? They bring wind, rain, flooding, and long-term power loss-all of which shut down factories that need stable electricity and clean water to make sterile drugs. Tornadoes hit harder but faster. In 2023, a tornado destroyed part of Pfizer’s plant in Rocky Mount, North Carolina. It knocked out production of 27 specific medicines. The shortage lasted 6-9 months. Not as wide as a hurricane, but just as deadly for patients relying on those exact drugs. Floods create cascading problems. In 2022, flooding hit Abbott’s infant formula plant in Michigan. That was already a crisis. The flood extended the shortage by eight weeks. People couldn’t find formula. Babies went hungry. And it’s not just the U.S. In 2018, a 7.3-magnitude earthquake in Iran killed 700 people and injured 10,000. While Iran’s drug manufacturing is more spread out, local clinics still ran out of painkillers, antibiotics, and IV fluids. The lesson? No country is immune. But the U.S. system is uniquely vulnerable because of how concentrated it is.

What’s Being Done-And What’s Not Working

After Hurricane Maria, the FDA started allowing emergency imports of drugs from Europe. But it took 28 days to get saline from Germany. That’s too long when patients are in ICU. Some hospitals are trying to adapt. Mayo Clinic spent nine months mapping every supplier-from the raw chemical vendor to the packaging plant. When Helene hit, they could quickly reroute orders. Their response time dropped by 65%. AI is helping too. Sensos.io used weather models to predict Helene’s impact on IV fluid supply 14 days ahead. A few hospitals used that warning to stockpile extra bags. They didn’t run out. But most hospitals can’t do this. Smaller clinics don’t have the staff, the budget, or the tech. The American Hospital Association found hospitals with 500+ beds are over three times more likely to have supply chain maps than small ones. That means rural patients, low-income patients, and elderly patients are the ones who suffer most.The Real Cost of Doing Nothing

The pharmaceutical industry is starting to feel the financial pressure. The market for supply chain resilience is expected to grow from $4.2 billion in 2024 to $9.7 billion by 2029. Companies are finally doing climate risk assessments-68% now, up from 22% in 2020. But only 31% have actually done anything about it. The FDA is pushing new rules. By 2025, manufacturers of critical drugs will need to:- Keep a 90-day emergency stockpile

- Submit a climate risk plan

- Prove they have backup manufacturing sites

What Needs to Happen Next

We need three things-right now: 1. Geographic diversification: No more single-factory dependence. The FDA’s new Critical Drug Resilience Program, launching in January 2025, rewards companies that spread production across three climate-resilient regions. That’s a start. 2. Strategic stockpiles: The government needs to store critical drugs-like insulin, saline, epinephrine, and antibiotics-in secure, climate-proof warehouses across different regions. A pilot program after Helene cut shortage duration by 40%. Scale that up. 3. Emergency fast-tracking: When a disaster hits, the FDA should be able to approve alternative suppliers in days, not weeks. Right now, the process is slow, bureaucratic, and full of red tape. And we need to stop pretending this is just a “pharmaceutical problem.” It’s a public health emergency. Cancer patients. Diabetics. Newborns. People on dialysis. They don’t get to wait for the next storm to pass.What You Can Do

As a patient or caregiver, you can’t rebuild a factory. But you can stay informed. - Check the FDA’s Drug Shortages page regularly. - Talk to your pharmacist about backup options-sometimes there are alternative brands or delivery methods. - If you rely on a drug that’s been in short supply, ask your doctor about having a small emergency stash. The system is broken. But it’s not hopeless. The data is clear. The solutions exist. What’s missing is the political will to act before the next storm hits.Why do natural disasters cause drug shortages?

Natural disasters damage or shut down pharmaceutical manufacturing plants, especially those located in disaster-prone areas. Many critical drugs are made in just one or two facilities. When a hurricane, flood, or tornado knocks out power, water, or transportation, production stops. Because the industry uses just-in-time inventory with little to no backup stock, shortages hit fast and hard.

Which drugs are most at risk during climate disasters?

Sterile injectables are the most vulnerable: IV fluids (saline, dextrose), antibiotics, insulin, epinephrine, and anesthetics. These require clean rooms, constant power, and precise conditions to produce. Generic drugs are especially at risk because they have low profit margins, so manufacturers don’t invest in backup capacity. Cancer drugs like vincristine and doxorubicin have also been in chronic shortage due to both economic and climate factors.

How long do drug shortages last after a disaster?

It depends on the disaster and the drug. Hurricanes often cause 6-18 month shortages because they destroy infrastructure like power grids and water systems. Tornadoes can cause 3-9 month shortages if they hit a single-facility producer. Bringing a new manufacturing line online takes 6-12 months. Specialized equipment can take 2-3 years to order and install.

Are there any solutions being implemented?

Yes. The FDA is launching a Critical Drug Resilience Program in January 2025 that rewards companies for spreading production across climate-resilient regions. Some hospitals are using AI to predict shortages before disasters hit. The Strategic National Stockpile is piloting emergency stockpiles of IV fluids and insulin in hurricane zones. But progress is slow, and most hospitals still lack the resources to prepare.

Can I get a backup supply of my medication?

If you rely on a drug that’s been in short supply, talk to your doctor or pharmacist. In some cases, they can help you get a small emergency supply-usually enough for 30 days. Some insurers allow early refills during declared emergencies. Never stop taking your medication without consulting your provider.

Will drug prices go up because of these changes?

Yes, likely. Building backup facilities, storing emergency stockpiles, and diversifying supply chains will raise production costs by 4-7% for critical drugs. But experts say that’s far cheaper than the cost of delayed cancer treatments, preventable infections, or deaths from insulin shortages. The real question isn’t whether prices will rise-it’s whether we can afford not to act.

Jerry Rodrigues

20 January, 2026 . 12:46 PM

This is the kind of systemic failure that keeps me up at night. One storm takes out a factory and people die because we chose profit over preparedness. No one talks about how we outsourced our medical security to a handful of coastal zones like it’s a stock portfolio.

Coral Bosley

22 January, 2026 . 05:56 AM

I watched my mother go without insulin for 11 days after Maria. They told her to use less because 'the supply chain is disrupted.' I’m not mad. I’m just done pretending this is about logistics and not about who gets to live in this country.

Melanie Pearson

23 January, 2026 . 13:37 PM

The FDA’s new rules are a joke. 90-day stockpiles? That’s not resilience-that’s window dressing. We need to nationalize critical drug production. Private corporations have proven they cannot be trusted with human lives. This isn’t capitalism. This is mass neglect dressed up as policy.

MARILYN ONEILL

24 January, 2026 . 11:42 AM

I don’t get why people are so dramatic. It’s just medicine. You can always get another prescription. My cousin took a different pill and lived just fine.

Uju Megafu

25 January, 2026 . 06:47 AM

AMERICA IS BROKEN. YOU PEOPLE LET THIS HAPPEN. YOU VOTED FOR THE PEOPLE WHO SOLD OUT YOUR KIDS’ INSULIN FOR QUARTERLY PROFITS. NOW YOU WANT TO TALK ABOUT ‘SOLUTIONS’? FIRST, APOLOGIZE. THEN BUILD THE STOCKPILES. THEN DON’T LET THE CEO’S YACHT BE MORE IMPORTANT THAN A BABY’S FORMULA.

Steve Hesketh

25 January, 2026 . 17:29 PM

I’ve worked in rural clinics in Nigeria. We’ve always had to improvise. No power? Use ice to keep meds cool. No IV bags? Reuse sterilized bottles. It’s not ideal. But we survive. The U.S. has all the money and tech in the world-and still can’t keep a diabetic alive. That’s not a supply chain problem. That’s a moral failure.

MAHENDRA MEGHWAL

26 January, 2026 . 17:36 PM

The structural vulnerabilities outlined here are well-documented. The economic disincentives for redundancy in generic drug manufacturing are profound. Regulatory frameworks must evolve beyond reactive compliance to proactive risk mitigation. The cost of inaction is measured in mortalities, not balance sheets.

lokesh prasanth

27 January, 2026 . 03:25 AM

just in time is for cars not lifesaving drugs lol